Listen to our 5 min Deep Dive Rachel Carson: The Quiet Crusader Who Sparked a Movement and Challenged the World

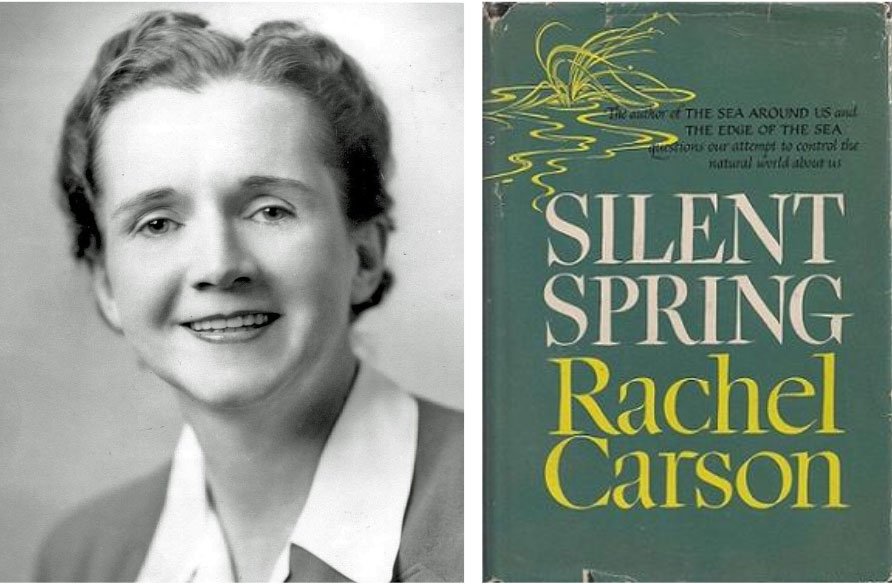

In the annals of environmental history, few figures loom as large or as consequential as Rachel Carson. A marine biologist by training and a lyrical writer by nature, Carson’s life and work culminated in the 1962 publication of Silent Spring, a book that not only exposed the perilous dark side of the chemical age but also ignited a global environmental movement. Her meticulous research and eloquent prose awakened a generation to the interconnectedness of all living things and the profound responsibility of humanity to protect the natural world. This awakening, however, came at a significant personal cost, as Carson was subjected to a vicious and coordinated campaign of disinformation and personal vilification by the very industries she dared to challenge.

Born in 1907 in the rural town of Springdale, Pennsylvania, Rachel Carson developed an early and profound connection with the natural world. Her mother, Maria McLean Carson, a well-educated woman for her time, instilled in her a “sense of wonder” that would become a guiding principle throughout her life.¹ As Carson would later write in her book dedicated to helping adults share nature with children: “A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood.”² This passion for nature led her to pursue a degree in biology at the Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University) and later a master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University. In an era when science was a male-dominated field, Carson’s academic achievements were remarkable.

Her professional career began at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (later the Fish and Wildlife Service), where she distinguished herself as a gifted writer, able to translate complex scientific concepts into accessible and engaging prose for the public. It was here that she honed the literary style that would make her famous—a unique blend of scientific accuracy and poetic sensibility. Her supervisor, recognizing her exceptional talent, encouraged her to submit her work to The Atlantic Monthly, launching her dual career as scientist and writer.³

The Sea Trilogy: Establishing a Voice

Carson’s early books formed what is now known as her “sea trilogy,” each exploring different aspects of marine environments with both scientific precision and literary grace. Under the Sea-Wind (1941), her first book, presented the ocean world from the perspective of its inhabitants—a sanderling named Silverbar, a mackerel called Scomber, and an eel named Anguilla. Through these characters, Carson conveyed complex ecological relationships in narrative form. Though initially unsuccessful commercially due to its release just before Pearl Harbor, the book demonstrated Carson’s innovative approach to nature writing.⁴

The Sea Around Us (1951) marked Carson’s breakthrough as a popular science writer. The book explored the physical and biological mysteries of the ocean, from its geological origins to its influence on human history. Carson wrote with characteristic elegance: “For the sea lies all about us. The commerce of all lands must cross it. The very winds that move over the lands have been cradled on its broad expanse and seek ever to return to it. The continents themselves dissolve and pass to the sea, in grain after grain of eroded land.”⁵ The book remained on the New York Times bestseller list for 86 weeks and won the National Book Award, establishing Carson as America’s preeminent nature writer.

The Edge of the Sea (1955) completed the trilogy, focusing on the ecology of the Atlantic shoreline. Here, Carson’s gift for making readers see familiar things with new eyes was fully realized. She described tide pools as “a world in miniature,” writing: “Tide pools contain mysterious worlds within their depths, where all the beauty of the sea is subtly suggested and portrayed in miniature.”⁶ The book pioneered the ecological approach to nature writing, emphasizing the interconnections between organisms and their environment rather than merely cataloging species.

The Making of Silent Spring

The genesis of Silent Spring was a letter Carson received in January 1958 from her friend Olga Owens Huckins, detailing the devastating loss of birdlife in her sanctuary following the aerial spraying of DDT for mosquito control. Huckins wrote of finding dead birds “with their beaks gaping open, and their claws drawn up to their breasts in agony.”⁷ This personal account, coupled with Carson’s growing concern over the indiscriminate use of synthetic pesticides developed during World War II, set her on a four-year journey of meticulous research.

Carson’s investigation revealed a pattern of ecological destruction and bureaucratic negligence that shocked even her. She corresponded with scientists worldwide, gathering evidence of pesticide impacts on wildlife and human health. Her files grew to include hundreds of scientific papers, government reports, and personal testimonies. She discovered that DDT persisted in the environment for years, accumulating in the fatty tissues of animals and concentrating as it moved up the food chain—a phenomenon now known as biomagnification.⁸

Silent Spring opened with “A Fable for Tomorrow,” a haunting vision of a town where spring arrived in silence, devoid of birdsong: “It was a spring without voices. On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.”⁹ This powerful imagery immediately captured readers’ imaginations and set the tone for the revelations to follow.

Carson was careful to emphasize that she was not advocating for the complete abandonment of pesticides, but rather for what she called “the other road”—biological controls and limited, targeted use of chemicals. She wrote: “The ‘control of nature’ is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.”¹⁰ Her central thesis was revolutionary for its time: that all life is interconnected and that to poison one part of the ecosystem is to ultimately poison it all.

The Industry Backlash

The publication of Silent Spring in September 1962 was met with a firestorm of controversy. The chemical industry, with annual pesticide sales of $300 million at stake, launched a massive campaign to discredit Carson and her work.¹¹ The National Agricultural Chemicals Association spent over $250,000 (equivalent to over $2 million today) on public relations efforts to counter the book’s influence.¹²

The attacks on Carson were often deeply personal and gendered. She was dismissed as a “hysterical woman,” an amateur, and even a communist sympathizer. Former Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson reportedly wondered why a “spinster” would be so concerned about genetics, implying that her unmarried, childless status somehow disqualified her from having valid concerns about the future.¹³ Chemical company spokesman Robert White-Stevens appeared on television to declare that “If man were to follow the teachings of Miss Carson, we would return to the Dark Ages, and the insects and diseases and vermin would once again inherit the earth.”¹⁴

Despite the relentless attacks, Carson remained steadfast. She calmly and eloquently defended her research in public appearances, including a pivotal CBS Reports television special titled “The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson” that aired on April 3, 1963. Watched by 10-15 million viewers, the program showed a composed Carson responding to her critics with scientific facts and quiet dignity. Her appearance, despite her visible frailty from cancer treatment, only enhanced her credibility and moral authority.¹⁵

Personal Cost and Quiet Courage

Throughout the writing of Silent Spring and the ensuing controversy, Carson was secretly battling breast cancer. Diagnosed in 1960, she underwent radiation treatment that left her weak and often in pain. She confided to her friend Dorothy Freeman: “I have felt so terribly that I just haven’t been able to do anything lately on the book, and the irony of it all is that I had been making such wonderful progress.”¹⁶ Yet she persevered, driven by what she saw as a moral imperative to complete her work.

Carson’s correspondence during this period reveals the depth of her commitment and the toll it took. To her editor Paul Brooks, she wrote: “In spite of illness, I know this has to be done. There would be no peace for me if I kept silent.”¹⁷ She worked when she could, often from her bed, determined to see the book through to publication.

Legislative and Cultural Impact

The impact of Silent Spring was immediate and transformative. President John F. Kennedy, who had read the book, ordered his Science Advisory Committee to investigate Carson’s claims. The committee’s report, issued in May 1963, largely vindicated Carson’s research and recommended tighter controls on pesticide use.¹⁸ Kennedy himself acknowledged the book’s influence, stating at a press conference that federal agencies were taking a closer look at pesticide use because of it.¹⁹

In the years following Carson’s death on April 14, 1964, her work inspired a wave of environmental legislation that transformed American environmental policy:

- The Wilderness Act (1964) protected millions of acres of federal land from development

- The National Environmental Policy Act (1969) required environmental impact assessments for federal projects

- The Clean Air Act (1970) established national air quality standards

- The creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (December 2, 1970) centralized environmental regulation

- The banning of DDT for domestic use (1972) directly vindicated Carson’s warnings

- The Endangered Species Act (1973) provided legal protection for threatened wildlife²⁰

Beyond legislation, Carson’s work fundamentally shifted public consciousness about humanity’s relationship with nature. She popularized the concept of ecology—the interconnectedness of all living things—making it accessible to ordinary citizens. Environmental historian Linda Lear notes that Carson “changed the way we look at the natural world and our place in it.”²¹

Literary Legacy and Environmental Ethics

Carson’s influence extended beyond policy into literature and philosophy. Her writing style—combining scientific rigor with lyrical prose—established a new standard for environmental writing. Authors like Annie Dillard, Barry Lopez, and Terry Tempest Williams acknowledge their debt to Carson’s pioneering work.²² Her concept of “the sense of wonder” became a cornerstone of environmental education, emphasizing emotional connection to nature as the foundation for conservation ethics.

In Silent Spring, Carson articulated an environmental ethic based on humility and reverence for life: “In each of my books I have tried to say that all life is interrelated, that each species has its own ties to others, and that all are related to the earth. This is the theme of The Sea Around Us and the other sea books, and it is also the message of Silent Spring.”²³

Continuing Relevance

Rachel Carson’s warnings about pesticide use remain relevant in an era of continued chemical pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss. Modern environmental challenges like neonicotinoid pesticides’ impact on bee populations, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and microplastic pollution echo the concerns she raised over 60 years ago.²⁴ Her emphasis on the precautionary principle—the idea that we should err on the side of caution when introducing new chemicals into the environment—continues to influence environmental policy debates.

Conservation biologist E.O. Wilson called Carson “the founding mother of the environmental movement,” noting that “She ranks with the greatest nature writers in American letters.”²⁵ Her courage in speaking truth to power, despite personal attacks and failing health, provides a model for contemporary environmental advocates facing similar industry pushback on issues from climate change to toxic chemicals.

Conclusion

Rachel Carson died in 1964, just two years after the publication of her most famous work. She did not live to see the full extent of the environmental revolution she had helped to ignite, but her legacy endures. She is remembered not only as a brilliant scientist and a gifted writer but also as a courageous and prescient voice who dared to challenge the prevailing orthodoxies of her time. At great personal cost, she awakened the world to the profound interconnectedness of life and our sacred responsibility to protect it.

In her final letter to Dorothy Freeman, written just months before her death, Carson reflected: “It is good to know that I shall live on even in the minds of many who do not know me and largely through association with things that are beautiful and lovely.”²⁶ Her quiet crusade, born of a deep love for the natural world, continues to inspire and empower environmental advocates to this day, reminding us that one voice, armed with truth and courage, can indeed change the world.

Notes

- Linda Lear, Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature (New York: Henry Holt, 1997), 16-18.

- Rachel Carson, The Sense of Wonder (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 42.

- Paul Brooks, The House of Life: Rachel Carson at Work (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1972), 18-20.

- William Souder, On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson (New York: Crown Publishers, 2012), 123-125.

- Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951), 15.

- Rachel Carson, The Edge of the Sea (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1955), 37.

- Frank Graham Jr., Since Silent Spring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 16.

- Lear, Rachel Carson, 366-370.

- Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962), 2.

- Carson, Silent Spring, 297.

- Robert B. Craig, “Banned and Banished: The DDT Ban Turns 40,” Environmental Health Perspectives 117, no. 6 (June 2009): A254-A256.

- Michael B. Smith, “‘Silence, Miss Carson!’ Science, Gender, and the Reception of Silent Spring,” Feminist Studies 27, no. 3 (Autumn 2001): 733-752.

- Lear, Rachel Carson, 429.

- CBS Reports, “The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson,” April 3, 1963, CBS Television Network.

- Brooks, House of Life, 293-295.

- Rachel Carson to Dorothy Freeman, January 23, 1962, in Always, Rachel: The Letters of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman, 1952-1964, ed. Martha Freeman (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 389.

- Rachel Carson to Paul Brooks, March 13, 1962, Rachel Carson Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- President’s Science Advisory Committee, Use of Pesticides (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963).

- “President’s News Conference,” May 15, 1963, in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: John F. Kennedy, 1963 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964), 409.

- J. Brooks Flippen, Nixon and the Environment (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000), 50-73.

- Linda Lear, introduction to Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002), xv.

- Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm, eds., The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996), 105-123.

- Rachel Carson, “Design for Nature Writing” (speech, American Association of University Women, New York, NY, December 7, 1963).

- Dave Goulson, “Neonicotinoids and Bees: What’s All the Buzz?” Significance 10, no. 3 (June 2013): 6-11.

- Edward O. Wilson, foreword to Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002), x.

- Rachel Carson to Dorothy Freeman, December 19, 1963, in Freeman, Always, Rachel, 507.