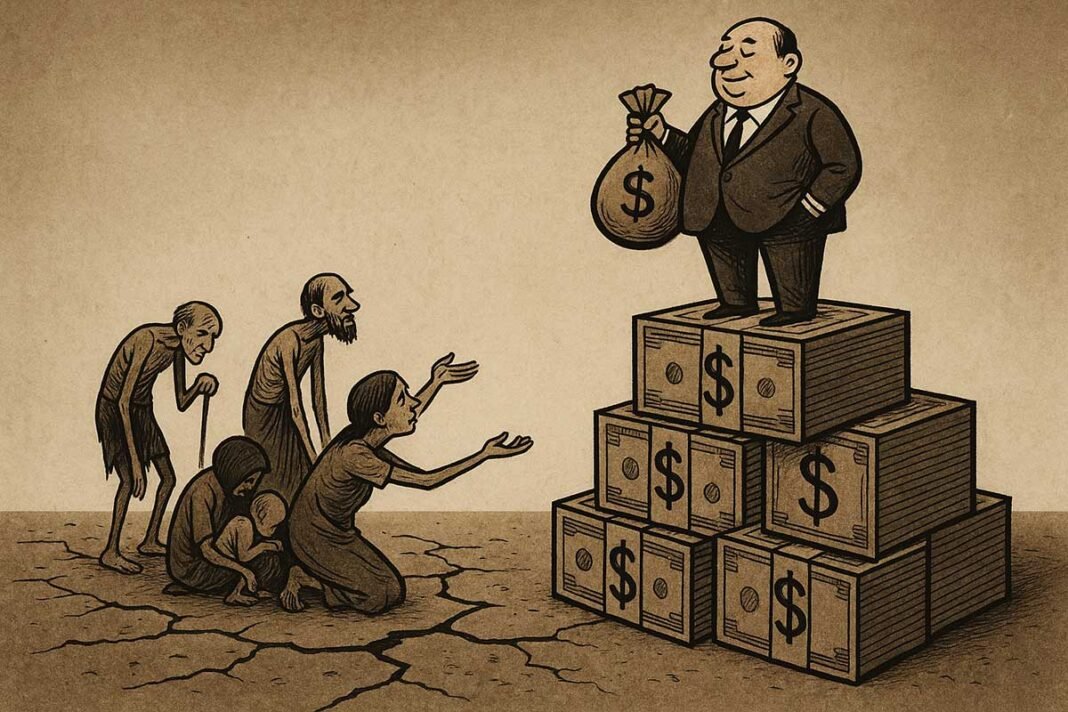

Global economic inequality has reached levels not seen since the Gilded Age of the early 20th century, with the richest 1% now controlling between 43% and 47.5% of all global wealth while 692 million people survive on less than $3 per day.¹ This concentration of resources represents not merely a statistical abstraction but a fundamental reorganization of human society that touches every aspect of contemporary life—from democratic governance to climate change, from health outcomes to social cohesion. The data reveals a world where the bottom 50% of humanity owns just 1.3% of total wealth, while the top 1% has captured more wealth than the bottom 95% combined.² These extremes have emerged through deliberate policy choices and institutional arrangements rather than natural market forces, creating what the World Inequality Lab describes as a “Second Gilded Age” with profound implications for humanity’s ability to address collective challenges.³

The historical trajectory of this inequality tells a story of political economy rather than economic inevitability. Since 1980, within-country inequality has emerged as the dominant form globally, reversing the mid-20th century trend toward greater equality within nations.⁴ The labor share of national income has declined precipitously across both advanced and emerging economies, with technology and globalization explaining approximately 75% of this decline in developed nations.⁵ Where the top 1% captured 17.8% of global income in 1980, they now command 20.6%, with the ultra-wealthy top 0.1% nearly doubling their share from 6.61% to 8.59%.⁶ This transformation coincided with specific policy shifts: top marginal tax rates plummeted from around 70% in the 1970s to 35-40% by the 2000s, union coverage collapsed from 27% to 11.6%, and financial deregulation enabled unprecedented wealth concentration through asset price inflation.⁷ The number of American billionaires alone jumped from 751 to 835 in just one year (2023-2024), while the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated wealth concentration with billionaire fortunes growing by $2 trillion in 2024—three times faster than the previous year.⁸

The Human Toll of Inequality Manifests Across Every Social Dimension

The social fabric of unequal societies shows systematic patterns of dysfunction that extend far beyond individual poverty. Research by Wilkinson and Pickett across 21 developed nations demonstrates an almost perfectly linear relationship between income inequality and an index of health and social problems.⁹ In highly unequal societies, people are significantly more likely to agree that “others would take advantage of you if they got the chance,” reflecting the erosion of generalized social trust that enables cooperative behavior and democratic governance.¹⁰ This breakdown in social cohesion creates what researchers term “prevalent latent animosities” and social disorganization, manifesting in higher crime rates, reduced civic participation, and weakened community bonds.¹¹

The health consequences of inequality operate through both material deprivation and psychosocial stress mechanisms. The World Health Organization’s 2024 report confirms that social determinants—where people are born, grow, live, and work—influence health outcomes more than genetic factors or healthcare access.¹² Life expectancy varies by 33 years between the highest and lowest countries, while within nations, disparities can span decades based on neighborhood and social group. Children in low-income countries are 13 times more likely to die before age five than those in high-income nations.¹³ Mental health effects are particularly pronounced, with systematic reviews in The Lancet finding that income inequality negatively affects population mental health through status anxiety, reduced social capital, and the stress of social comparison.¹⁴ These health disparities create intergenerational cycles, as maternal education levels and childhood poverty predict lifelong health and economic outcomes.

Educational opportunity follows similar patterns of stratification. UNESCO research reveals that one additional year of maternal education influences daughters’ education more strongly than sons’ in low-income countries, with coefficients of 0.59 versus 0.54 respectively.¹⁵ The gap in human capital expands dramatically through childhood—from 1.36 times at birth to 2.89 times by the end of compulsory education between rich and poor families.¹⁶ Globally, 258 million children remain out of school, with rates of 31% in sub-Saharan Africa versus 3% in Europe and North America.¹⁷ This educational inequality bridges the gap between current inequality and future immobility, as countries with higher inequality consistently show lower intergenerational mobility—a relationship economists call the “Great Gatsby Curve.”¹⁸ Housing segregation compounds these effects, with research showing that more than 50 years after the Fair Housing Act, most U.S. communities remain racially segregated, and homes in majority-Black neighborhoods are valued 23% lower even after controlling for quality.¹⁹

Geographic Patterns Reveal Persistent Structural Divides

The geography of global inequality reflects historical legacies and contemporary power structures that resist change. South Africa maintains the world’s highest inequality with a Gini coefficient of 63.0, where the richest 0.01%—just 3,500 individuals—own 15% of total wealth while the bottom 60% hold only 7%.²⁰ This extreme concentration stems directly from apartheid’s institutional architecture, which created separate economic systems that persist despite political transformation. Latin America and the Caribbean show similarly entrenched patterns with an average Gini of 48.3, rooted in colonial land distribution and reinforced by contemporary elite capture of political systems.²¹ The United States stands as the only high-income economy besides Chile, Panama, and Uruguay with high inequality (Gini 41.1), where the top 1% averaged 40 times more income than the bottom 90% in 2015.²²

In stark contrast, the Nordic countries have maintained Gini coefficients between 0.25 and 0.28 through distinctive institutional arrangements.²³ Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, and Denmark achieve low inequality primarily through wage compression rather than redistribution—a critical distinction that challenges conventional understanding. Their two-tier bargaining systems, where sectoral negotiations set wage floors followed by firm-level adjustments, create remarkably compressed wage distributions.²⁴ Sweden’s apparent paradox of low income inequality but high wealth inequality (Gini 0.79-0.86 for wealth) illustrates how different forms of inequality interact.²⁵ Japan maintains moderate inequality (Gini 32-35) through strong fiscal redistribution despite facing similar technological and global pressures as other advanced economies.²⁶

Urban-rural divides add another dimension to spatial inequality. In China, urban inequality (Gini ~32) remains significantly lower than rural inequality, while in the United States, metropolitan areas experienced larger inequality increases from 1970-2016 than non-metropolitan regions.²⁷ Latin America shows the opposite pattern, with rural inequality exceeding urban levels.²⁸ Infrastructure gaps mean rural residents face 20 minutes to 2 hours longer travel times to essential services, while foreign investment concentration in urban areas with better infrastructure continuously widens these gaps.²⁹ The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted three decades of declining global inequality between countries, with the largest increase since 1990 as wealthy nations recovered faster than developing economies.³⁰

Seven Structural Drivers Perpetuate and Amplify Inequality

The systemic causes of growing inequality emerge from specific institutional changes and policy decisions rather than inevitable market forces. Financialization stands as a primary driver, with the financial sector wage premium growing from 1.1 times comparable workers in the 1950s-1980s to 1.8 times today.³¹ Non-financial corporations increasingly engage in financial activities rather than productive investment, leading to stock buybacks that benefit shareholders while constraining wages. With 89% of stocks owned by the richest 10%, asset price inflation directly translates to wealth concentration.³² During the 2020 pandemic alone, the richest 1% gained $5.6 trillion, with 70% coming from stock market gains, while the bottom 90% gained only $1.2 trillion.³³

Tax policy changes since the 1980s systematically shifted the burden from capital to labor. Research by Hope and Limberg analyzing 18 OECD countries over 50 years found that tax cuts for the rich increase income inequality by 0.7+ percentage points per major reform, with no evidence of trickle-down benefits to growth or employment.³⁴ The preferential treatment of capital gains over labor income, weakened estate taxes, and reduced progressivity enabled greater wealth accumulation at the top. Lower tax rates also incentivized rent-seeking behavior, as high earners bargain more aggressively for compensation when they can keep larger shares.³⁵

Technological change has created a “task-based” transformation of work that goes beyond traditional skill-biased technical change. MIT research by Acemoglu and Restrepo found that after 1987, automation displaced jobs 16% faster than it created new opportunities, with only 10% “reinstatement” of displaced positions.³⁶ Many automated systems represent “so-so technologies” that reduce labor costs without improving productivity, like self-checkout systems that simply shift work to customers.³⁷ This technological displacement interacts with globalization’s impact—trade played an “appreciable but modest” role in wage inequality according to NBER studies, but the “China syndrome” of import competition devastated specific communities and accelerated the hollowing out of middle-class manufacturing jobs.³⁸

The decline of labor unions from 27% coverage in 1979 to 11.6% in 2019 (below 7% in the private sector) explains 33.1% of the growth in wage inequality between high earners and median workers according to Economic Policy Institute research.³⁹ Unions compress wages within firms and industries while providing political counterweight to corporate interests. Market concentration has increased across most U.S. industries since the 1980s, with average corporate markups tripling from 21% above marginal cost to 61% today.⁴⁰ While concentration explains only 3.5-10% of wage inequality trends, monopsony power in labor markets reduces worker bargaining power.⁴¹ These factors interact with rent-seeking behavior and regulatory capture, where wealthy interests shape policy for private benefit, creating self-reinforcing cycles of inequality.⁴²

Solutions Emerge from Evidence Across Multiple Domains

The landscape of policy responses reveals both promising innovations and persistent challenges in addressing inequality. Progressive wealth taxation shows significant revenue potential, with Tax Justice Network estimates of $2+ trillion annually from global implementation—a 7% average increase in national budgets across 172 countries.⁴³ Saez and Zucman’s modeling demonstrates that a moderate 3% wealth tax above $1 billion since 1982 would have reduced the top 400 Americans’ wealth share from 3.5% to 2%.⁴⁴ However, implementation challenges have led many countries to repeal wealth taxes due to high administrative costs, capital flight, and enforcement difficulties. Only Norway, Spain, and Switzerland maintain comprehensive wealth taxes today, down from 12 European countries in 1995.⁴⁵

Universal Basic Income trials provide compelling evidence against common objections. Kenya’s GiveDirectly study, the world’s largest UBI experiment involving 23,000+ individuals, found no “laziness effect”—recipients worked the same hours but shifted toward entrepreneurship, increasing household income by 50% without causing inflation.⁴⁶ Finland’s experiment with 2,000 unemployed participants receiving €560 monthly showed improved life satisfaction, reduced mental strain, and modest employment gains.⁴⁷ Stockton, California’s pilot demonstrated that recipients primarily spent funds on groceries (37%) and bills (32%), with full-time employment actually increasing as UBI provided time for job searching.⁴⁸ Crucially, long-term commitments and lump-sum transfers significantly outperformed short-term monthly payments in generating productive investments.

Worker cooperatives offer an alternative ownership model with demonstrated success. U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives data shows 900+ democratic workplaces employing 10,000+ workers, with average wages of $19.67 versus $12.67 minimum wage in high co-op states, plus an additional $8,241 average profit distribution per worker-owner.⁴⁹ These enterprises maintain 1:1 or 2:1 pay ratios compared to 351:1 in top corporations, with equal or superior survival rates and productivity compared to conventional firms.⁵⁰ Italy’s Marcora Law provides a scalable framework, using unemployment benefits to capitalize worker buyouts of failing businesses, successfully preserving community economic assets while reducing unemployment.⁵¹

Minimum wage increases show positive effects when properly implemented. Seattle’s gradual increase to $15 (now $20.76 in 2025) resulted in low-wage workers gaining approximately $12 weekly despite modest hour reductions, with 99% of businesses surviving implementation and no significant job losses or relocations.⁵² The UK’s national minimum wage, with a higher “bite” at 39% of mean wages versus 27% in the U.S., significantly reduced wage inequality at the bottom of the distribution without major employment effects.⁵³ Universal public services, from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance achieving 99.9% coverage to the Nordic countries’ comprehensive welfare systems, demonstrate how universal approaches reduce inequality more effectively than means-tested alternatives while maintaining higher public satisfaction.⁵⁴

Critical Perspectives Reveal Fundamental Disagreements

The theoretical landscape of inequality scholarship reflects deep philosophical divisions about markets, justice, and human nature. Neoclassical economics maintains that inequality reflects differences in marginal productivity and human capital, with markets efficiently allocating resources based on individual contributions.⁵⁵ This perspective emphasizes how inequality provides necessary incentives for innovation and growth, warning that redistribution reduces efficiency through distorted incentives. However, empirical evidence increasingly challenges these assumptions—Piketty’s demonstration that wealth grows faster than income (r > g) in slow-growth economies contradicts marginal productivity theory, while persistent inequality despite human capital convergence suggests power relations matter more than pure productivity differences.⁵⁶

Keynesian analysis focuses on how inequality affects aggregate demand and macroeconomic stability. Since wealthy households have lower marginal propensities to consume, inequality can create chronic demand deficiency and economic stagnation.⁵⁷ This framework explains how inequality becomes self-reinforcing through reduced investment opportunities when purchasing power concentrates at the top. Post-Keynesian extensions emphasize financial instability and effective demand, showing how inequality drives speculative bubbles and economic crises.

Marxist and neo-Marxist scholars argue inequality is inherent to capitalism through exploitation of labor by capital owners.⁵⁸ They emphasize how class position—ownership of means of production—determines distribution more than individual characteristics, with capitalism necessarily producing inequality as a “functional component” of accumulation. Contemporary neo-Marxists analyze financialization as a new form of surplus extraction and examine how global value chains enable exploitation across borders.⁵⁹ Institutional economists shift focus to power relationships and institutional arrangements, arguing that rent-seeking behavior creates unproductive wealth accumulation while quality of institutions determines whether inequality stems from productive innovation or extractive activities.⁶⁰

Feminist economics reveals how traditional analysis ignores gender-based inequalities and unpaid care work, which represents an estimated 63% of UK GDP in 2016.⁶¹ This perspective highlights how markets systematically undervalue work performed predominantly by women and how macroeconomic models fail to account for the “reproductive economy” essential to all market activity. Post-colonial economics traces contemporary global inequality to colonial extraction and ongoing unequal exchange, showing how imperial transfers of value maintain wealth concentration in former colonial powers through trade, debt, and institutional arrangements.⁶² Modern Monetary Theory argues that governments with monetary sovereignty face no financial constraints on spending, proposing job guarantee programs to achieve full employment and reduce inequality directly through public employment rather than redistribution.⁶³

Policy Momentum Confronts Implementation Challenges

Recent international initiatives reveal both unprecedented cooperation and persistent obstacles in addressing inequality. The OECD’s historic agreement on a 15% minimum corporate tax rate, initially endorsed by 136+ countries, represents the most significant multilateral tax cooperation ever achieved.⁶⁴ Yet implementation faces severe challenges—the Trump administration’s 2025 withdrawal threat and compromise allowing U.S. exemptions undermines the framework’s universality. While 18 EU member states implemented the rules by 2024, five deferred until 2029, and the failure to meet Pillar One deadlines on profit reallocation maintains the standoff over digital services taxes.⁶⁵

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 10 shows mixed progress at best. While incomes of the poorest 40% had grown faster than national averages in many countries before 2020, COVID-19 caused the largest rise in between-country inequality in three decades.⁶⁶ Record refugee numbers (37.8 million), rising discrimination, and over one in five EU residents at risk of poverty or social exclusion demonstrate persistent challenges.⁶⁷ The pandemic revealed how quickly progress can reverse—despite massive fiscal responses exceeding $12 trillion globally, recovery patterns reinforced existing disparities as advanced economies recovered faster than emerging markets.⁶⁸

National experiments provide clearer successes. The Biden administration’s “whole-of-government” equity approach, embedding equity considerations across 90 federal agencies, achieved measurable impacts including a 40%+ reduction in property appraisal gaps in communities of color and record small disadvantaged business contracting.⁶⁹ The American Rescue Plan boosted after-tax income by 20.4% for the lowest quintile households, demonstrating fiscal policy’s potential for rapid inequality reduction.⁷⁰ Portugal’s post-2015 reversal of austerity—restoring public sector wages and social benefits while attracting foreign investment—achieved the highest GDP growth of the 21st century while reducing deficits from 8 billion to 2 billion euros, challenging orthodox economic assumptions about the necessity of austerity.⁷¹

Inequality Interweaves with Humanity’s Existential Challenges

The connections between economic inequality and global challenges create cascading crises that amplify each other. Climate change both drives and is driven by inequality through multiple pathways. The top 10% of global income earners produce 48% of greenhouse gas emissions while the bottom 50% contribute only 12%, with the top 1% responsible for 23% of emissions growth since 1990.⁷² Stanford research demonstrates global warming has increased inequality between countries by 25% since 1961, making the world’s poorest countries 17-30% poorer than they would have been without climate change.⁷³ This creates a vicious cycle where inequality fuels emissions through consumption patterns of the wealthy while climate impacts hit the poorest hardest, widening gaps further.

These climate-inequality feedbacks interact with other global challenges. Environmental degradation correlates with both income and power inequality—countries with more unequal distributions show higher rates of species extinction and deforestation.⁷⁴ Communities of color disproportionately face environmental hazards, creating “sacrifice zones” where industrial pollution concentrates.⁷⁵ Migration pressures intensify as climate change displaces millions from the most vulnerable regions, with research showing hate crimes and xenophobic responses are significantly stronger in high-inequality localities.⁷⁶ Food insecurity, affecting 1 in 9 U.S. households despite abundant production, has “economic root causes” in low wages and residential segregation rather than absolute scarcity.⁷⁷

Perhaps most concerning for long-term stability, economic inequality emerges as one of the strongest predictors of democratic erosion according to 2024 PNAS research.⁷⁸ Even wealthy, longstanding democracies prove vulnerable to backsliding when highly unequal, as inequality creates grievances that authoritarian leaders exploit while facilitating elite capture of political processes. The correlation extends to conflict—while individual-level inequality shows weak links to armed conflict, group-based horizontal inequality between ethnic, religious, or regional groups strongly predicts violence.⁷⁹ Health crises like COVID-19 demonstrate how inequality shapes pandemic outcomes, with consistent evidence across 95 studies showing higher mortality in areas of socioeconomic disadvantage.⁸⁰

Historical Precedents Demonstrate Transformation Remains Possible

The historical record provides both cautionary tales and inspiring examples of successful inequality reduction. The Nordic model’s achievement of the world’s lowest inequality levels (Gini 0.25-0.28) emerged not from redistribution alone but from wage compression through highly coordinated bargaining systems.⁸¹ Two-tier negotiations—sectoral agreements setting wage floors followed by firm-level adjustments—created remarkable wage equality while maintaining economic dynamism. Universal public services and high union density (ranging from 50% to 70%) provide the institutional foundation, while cultural norms of “social solidarity” enable high tax compliance and public support for egalitarian policies.⁸²

Latin America’s “pink tide” demonstrated that significant inequality reduction is possible even in highly unequal societies. Brazil’s Bolsa Família program lifted 36 million people from extreme poverty at just 0.6% of GDP, halving extreme poverty from 9.7% to 4.3% while reducing the Gini coefficient by 15%.⁸³ The program’s success relied on effective targeting through the Cadastro Único registry, integration with health and education services, and the fiscal space provided by the commodity boom. Bolivia under Evo Morales achieved even more dramatic results—poverty fell from 60% to 35% between 2006 and 2017, with extreme poverty more than halving from 38% to 15%.⁸⁴ Nationalization of natural resources, land redistribution to indigenous families, and universal cash transfers combined with 4.8% average annual GDP growth to transform one of Latin America’s poorest countries.

South Korea’s experience from the 1960s-1990s challenges assumptions about the inequality-growth tradeoff. Starting with relatively equal distribution due to comprehensive land reform in the 1950s, Korea maintained low inequality despite 7% annual GDP growth for three decades.⁸⁵ Massive investment in education—achieving the highest enrollment rates for comparable GDP per capita by 1961—combined with export-oriented industrialization and demographic transition to enable broad-based prosperity.⁸⁶ The U.S. New Deal and postwar period similarly show how crisis can enable transformative change. Roosevelt’s combination of banking reform, Social Security, job creation through the WPA, and labor protections created the institutional foundation for the “Great Compression” of inequality from the 1940s-1970s, demonstrating that even highly unequal societies can achieve dramatic redistribution through political will and comprehensive reform.⁸⁷

Conclusion: The Architecture of Inequality Demands Systemic Reconstruction

The evidence reveals economic inequality not as a natural market outcome but as the product of specific institutional arrangements and policy choices that can be changed. The concentration of global wealth—where the richest 1% controls nearly half of all resources while billions struggle in poverty—represents a fundamental challenge to human flourishing and planetary survival. This extreme inequality undermines social cohesion, democratic governance, public health, educational opportunity, and humanity’s capacity to address existential threats like climate change. Yet the successful experiences of countries from Scandinavia to South Korea, from Portugal to Bolivia, demonstrate that significant inequality reduction remains achievable through various pathways.

The research points toward integrated solutions rather than single policies: progressive taxation to limit wealth concentration, universal public services to ensure basic dignity, democratic ownership models to share prosperity, and strong labor institutions to balance corporate power. The false choice between equality and efficiency dissolves when we recognize that extreme inequality itself creates inefficiency through underinvestment in human potential, political instability, and social fragmentation. As inequality reaches levels not seen since the Gilded Age, humanity faces a choice between accepting a new feudalism of inherited advantage or building institutions that enable broad-based flourishing. The historical record suggests transformation is possible, but only through the kind of comprehensive political and economic reconstruction that previous inequality crises demanded. Whether democratic societies can muster such transformation before inequality undermines democracy itself may determine not just economic futures but the trajectory of human civilization in an era of compounding global challenges.

Notes

¹ World Inequality Database, “10 Facts on Global Inequality in 2024,” WID, January 2024, https://wid.world/news-article/10-facts-on-global-inequality-in-2024/.

² Oxfam International, “World’s Top 1% Own More Wealth than 95% of Humanity,” Press Release, September 2024, https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/worlds-top-1-own-more-wealth-95-humanity.

³ Lucas Chancel et al., World Inequality Report 2022 (Paris: World Inequality Lab, 2022), 10-15.

⁴ Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016), 46-52.

⁵ Mai Chi Dao et al., “Why Is Labor Receiving a Smaller Share of Global Income?” IMF Working Papers 2017, no. 169 (2017): 1-47.

⁶ World Inequality Database, “10 Facts on Global Inequality.”

⁷ David Hope and Julian Limberg, “The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich,” Socio-Economic Review 20, no. 2 (2022): 539-559.

⁸ Chuck Collins, “Billionaire Wealth Surges by $2 Trillion in 2024,” Inequality.org, January 20, 2025, https://inequality.org/facts/global-inequality/.

⁹ Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009), 18-30.

¹⁰ Fredrik Solt, “Economic Inequality and Democratic Political Engagement,” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 1 (2008): 48-60.

¹¹ Pablo Beramendi et al., “How Socio-Economic Inequality Affects Individuals’ Civic Engagement,” Socio-Economic Review 21, no. 1 (2023): 665-698.

¹² World Health Organization, World Report on Social Determinants of Health Equity (Geneva: WHO, 2024), 12-45.

¹³ Ibid., 78-82.

¹⁴ Vikram Patel et al., “Income Inequality and Mental Illness-Related Morbidity and Resilience: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” The Lancet Psychiatry 4, no. 7 (2017): 554-562.

¹⁵ UNESCO, “The Cycle of Intergenerational Transmission of Education Inequality Can Be Broken,” 2020 GEM Report, 2020, https://gem-report-2020.unesco.org/.

¹⁶ Abdullah Coşkun and Hakan Sezgin, “The Impact of Education on Income Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility,” China Economic Review 38 (2016): 253-266.

¹⁷ United Nations, “Recognizing and Overcoming Inequity in Education,” UN Chronicle, 2024, https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/.

¹⁸ Miles Corak, “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2013): 79-102.

¹⁹ Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), 153-169.

²⁰ World Bank, “The Geography of High Inequality: Monitoring the World Bank’s New Indicator,” World Bank Blogs, October 2024, https://blogs.worldbank.org/.

²¹ CEPAL, Social Panorama of Latin America 2023 (Santiago: United Nations, 2023), 45-67.

²² Congressional Budget Office, The Distribution of Household Income, 2019 (Washington: CBO, 2022), 23-34.

²³ OECD, Income Inequality in the Nordics from a European Perspective (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2024), 12-18.

²⁴ Jon Erik Dølvik and Jørgen Steen, “The Nordic Model and Income Equality: Myths, Facts, and Policy Lessons,” CEPR VoxEU, March 2024, https://cepr.org/voxeu/.

²⁵ Statistics Sweden, Wealth Statistics 2023 (Stockholm: SCB, 2024), 34-38.

²⁶ International Monetary Fund, “Sustainable Path to Inclusive Growth in Japan: How to Tackle Income Inequality?” IMF Staff Country Reports 2024, no. 119 (2024): 45-67.

²⁷ Katherine Thiede and Shannon Monnat, “Income Inequality across the Rural-Urban Continuum in the United States, 1970–2016,” Rural Sociology 86, no. 4 (2021): 899-937.

²⁸ World Bank, “LAC Equity Lab: Income Inequality – Urban/Rural Inequality,” 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/.

²⁹ Michael Storper et al., “Urban Inequalities in the 21st Century Economy,” Applied Geography 117 (2020): 102-188.

³⁰ Francisco H. G. Ferreira, “Inequality in the Time of COVID-19,” IMF Finance & Development 58, no. 2 (2021): 20-23.

³¹ Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef, “Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Finance Industry: 1909–2006,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, no. 4 (2012): 1551-1609.

³² Edward N. Wolff, “Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962 to 2019,” NBER Working Paper No. 28383 (2021): 12-23.

³³ Federal Reserve, “Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989,” DFA Quarterly Report, Q4 2023.

³⁴ Hope and Limberg, “Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts,” 545-550.

³⁵ Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Rent Seeking and the Making of an Unequal Society,” in The Price of Inequality (New York: Norton, 2012), 28-51.

³⁶ Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, “Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality,” Econometrica 90, no. 5 (2022): 1973-2016.

³⁷ Ibid., 1980-1985.

³⁸ David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson, “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” American Economic Review 103, no. 6 (2013): 2121-2168.

³⁹ Josh Bivens et al., “The Enormous Impact of Eroded Collective Bargaining on Wages,” Economic Policy Institute, April 2021, https://www.epi.org/.

⁴⁰ Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout, and Gabriel Unger, “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135, no. 2 (2020): 561-644.

⁴¹ Suresh Naidu and Eric A. Posner, “Labor Monopsony and the Limits of the Law,” Journal of Human Resources 57, no. S (2022): S284-S323.

⁴² Anne O. Krueger, “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society,” American Economic Review 64, no. 3 (1974): 291-303.

⁴³ Tax Justice Network, “Taxing Extreme Wealth: What Countries Around the World Could Gain from Progressive Wealth Taxes,” Report, December 2023, https://taxjustice.net/.

⁴⁴ Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Progressive Wealth Taxation,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2019, no. 2 (2019): 437-511.

⁴⁵ OECD, “The Role and Design of Net Wealth Taxes in the OECD,” OECD Tax Policy Studies No. 26 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018), 45-67.

⁴⁶ GiveDirectly, “Early Findings from the World’s Largest UBI Study,” 2023 Report, https://www.givedirectly.org/2023-ubi-results/.

⁴⁷ Kela, “Results of Finland’s Basic Income Experiment,” Social Insurance Institution of Finland, 2020.

⁴⁸ SEED, “Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration: Final Report,” 2021.

⁴⁹ U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, “Worker Cooperative Economic Census,” USFWC, 2023.

⁵⁰ Virginie Pérotin, “Worker Cooperatives: Good, Sustainable Jobs in the Community,” Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity 2, no. 2 (2013): 34-47.

⁵¹ Marcella Corsi and Carlo D’Ippoliti, “The Productivity of Worker Cooperatives: The Italian Marcora Law,” Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 94, no. 1 (2023): 175-197.

⁵² Jacob Vigdor et al., “The Seattle Minimum Wage Study: Final Report,” Evans School of Public Policy, University of Washington, 2022.

⁵³ Alan Manning, “The UK National Minimum Wage at Age 22,” Centre for Economic Performance, LSE, 2021.

⁵⁴ Tsung-Mei Cheng, “Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance: Achievements and Challenges,” Annals of Internal Medicine 172, no. 9 (2020): 618-619.

⁵⁵ N. Gregory Mankiw, “Defending the One Percent,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2013): 21-34.

⁵⁶ Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 25-27.

⁵⁷ John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (London: Macmillan, 1936), 373-374.

⁵⁸ Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1, trans. Ben Fowkes (London: Penguin, 1976 [1867]), 341-416.

⁵⁹ David Harvey, “Marx on Income Inequality Under Capitalism,” Global Policy Journal, February 14, 2022, https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/.

⁶⁰ Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (New York: Crown, 2012), 73-75.

⁶¹ Nancy Folbre, “Measuring Care: Gender, Empowerment, and the Care Economy,” Journal of Human Development 7, no. 2 (2006): 183-199.

⁶² Jason Hickel, “The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions” (London: Heinemann, 2017), 145-167.

⁶³ Stephanie Kelton, The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), 234-256.

⁶⁴ OECD, “138 Countries and Jurisdictions Agree Historic Milestone to Implement Global Tax Deal,” Press Release, July 2023, https://www.oecd.org/.

⁶⁵ PwC, “Pillar Two Country Tracker,” PwC Global Tax Services, 2024, https://www.pwc.com/.

⁶⁶ United Nations, “Goal 10: Reduce Inequality Within and Among Countries,” Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024.

⁶⁷ Ibid.

⁶⁸ World Bank, “WDR 2022 Chapter 1: Introduction – The Economic Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis,” 2022.

⁶⁹ White House, “FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces Key Progress on Efforts to Close the Racial Wealth Gap,” April 12, 2024.

⁷⁰ Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “American Rescue Plan Act: Impact on Poverty and Income,” CBPP Analysis, 2023.

⁷¹ Fraser Institute, “Austerity—Not Increased Spending—Helped Lay the Groundwork for Portugal’s Recovery,” Commentary, 2024.

⁷² Noah Diffenbaugh and Marshall Burke, “Global Warming Has Increased Global Economic Inequality,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 20 (2019): 9808-9813.

⁷³ Ibid., 9810-9812.

⁷⁴ James K. Boyce, “Inequality as a Cause of Environmental Degradation,” Ecological Economics 11, no. 3 (1994): 169-178.

⁷⁵ Robert D. Bullard, Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality, 3rd ed. (Boulder: Westview Press, 2000), 45-67.

⁷⁶ Andreas Steinmayr, “Contact versus Exposure: Refugee Presence and Voting for the Far Right,” Review of Economics and Statistics 103, no. 2 (2021): 310-327.

⁷⁷ Craig Gundersen and James P. Ziliak, “Food Insecurity Has Economic Root Causes,” Nature Food 3, no. 8 (2022): 567-569.

⁷⁸ Tarik Abou-Chadi and Markus Wagner, “Economic Inequality Leads to Democratic Erosion, Study Finds,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, no. 3 (2024): e2312456121.

⁷⁹ Frances Stewart, Horizontal Inequalities and Conflict: Understanding Group Violence in Multiethnic Societies (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 123-145.

⁸⁰ Claire Bambra et al., “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74, no. 11 (2020): 964-968.

⁸¹ Erling Barth, Alex Bryson, and Harald Dale-Olsen, “Union Density Effects on Productivity and Wages,” Economic Journal 130, no. 631 (2020): 1898-1936.

⁸² Jon Pareliussen et al., “Income Inequality in the Nordics from an OECD Perspective,” Nordic Economic Policy Review 2018 (Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, 2018), 17-57.

⁸³ World Bank, “Bolsa Família: Brazil’s Quiet Revolution,” Opinion, November 4, 2013, https://www.worldbank.org/.

⁸⁴ Nancy Postero, The Indigenous State: Race, Politics, and Performance in Plurinational Bolivia (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), 89-112.

⁸⁵ Myung Soo Cha, “The Economic History of Korea,” EH.net Encyclopedia, March 2020, https://eh.net/.

⁸⁶ Alice H. Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 234-256.

⁸⁷ Claudia Goldin and Robert A. Margo, “The Great Compression: The Wage Structure in the United States at Mid-Century,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, no. 1 (1992): 1-34.

Bibliography

Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Markus Wagner. “Economic Inequality Leads to Democratic Erosion, Study Finds.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121, no. 3 (2024): e2312456121.

Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown, 2012.

Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. “Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality.” Econometrica 90, no. 5 (2022): 1973-2016.

Amsden, Alice H. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” American Economic Review 103, no. 6 (2013): 2121-2168.

Bambra, Claire, Ryan Riordan, John Ford, and Fiona Matthews. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74, no. 11 (2020): 964-968.

Barth, Erling, Alex Bryson, and Harald Dale-Olsen. “Union Density Effects on Productivity and Wages.” Economic Journal 130, no. 631 (2020): 1898-1936.

Beramendi, Pablo, et al. “How Socio-Economic Inequality Affects Individuals’ Civic Engagement.” Socio-Economic Review 21, no. 1 (2023): 665-698.

Bivens, Josh, et al. “The Enormous Impact of Eroded Collective Bargaining on Wages.” Economic Policy Institute, April 2021. https://www.epi.org/.

Boyce, James K. “Inequality as a Cause of Environmental Degradation.” Ecological Economics 11, no. 3 (1994): 169-178.

Bullard, Robert D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. 3rd ed. Boulder: Westview Press, 2000.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “American Rescue Plan Act: Impact on Poverty and Income.” CBPP Analysis, 2023.

CEPAL. Social Panorama of Latin America 2023. Santiago: United Nations, 2023.

Cha, Myung Soo. “The Economic History of Korea.” EH.net Encyclopedia, March 2020. https://eh.net/.

Chancel, Lucas, et al. World Inequality Report 2022. Paris: World Inequality Lab, 2022.

Cheng, Tsung-Mei. “Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance: Achievements and Challenges.” Annals of Internal Medicine 172, no. 9 (2020): 618-619.

Collins, Chuck. “Billionaire Wealth Surges by $2 Trillion in 2024.” Inequality.org, January 20, 2025. https://inequality.org/facts/global-inequality/.

Congressional Budget Office. The Distribution of Household Income, 2019. Washington: CBO, 2022.

Corak, Miles. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2013): 79-102.

Corsi, Marcella, and Carlo D’Ippoliti. “The Productivity of Worker Cooperatives: The Italian Marcora Law.” Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 94, no. 1 (2023): 175-197.

Coşkun, Abdullah, and Hakan Sezgin. “The Impact of Education on Income Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility.” China Economic Review 38 (2016): 253-266.

Dao, Mai Chi, et al. “Why Is Labor Receiving a Smaller Share of Global Income?” IMF Working Papers 2017, no. 169 (2017): 1-47.

De Loecker, Jan, Jan Eeckhout, and Gabriel Unger. “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135, no. 2 (2020): 561-644.

Diffenbaugh, Noah, and Marshall Burke. “Global Warming Has Increased Global Economic Inequality.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 20 (2019): 9808-9813.

Dølvik, Jon Erik, and Jørgen Steen. “The Nordic Model and Income Equality: Myths, Facts, and Policy Lessons.” CEPR VoxEU, March 2024. https://cepr.org/voxeu/.

Federal Reserve. “Distribution of Household Wealth in the U.S. since 1989.” DFA Quarterly Report, Q4 2023.

Ferreira, Francisco H. G. “Inequality in the Time of COVID-19.” IMF Finance & Development 58, no. 2 (2021): 20-23.

Folbre, Nancy. “Measuring Care: Gender, Empowerment, and the Care Economy.” Journal of Human Development 7, no. 2 (2006): 183-199.

Fraser Institute. “Austerity—Not Increased Spending—Helped Lay the Groundwork for Portugal’s Recovery.” Commentary, 2024.

GiveDirectly. “Early Findings from the World’s Largest UBI Study.” 2023 Report. https://www.givedirectly.org/2023-ubi-results/.

Goldin, Claudia, and Robert A. Margo. “The Great Compression: The Wage Structure in the United States at Mid-Century.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, no. 1 (1992): 1-34.

Gundersen, Craig, and James P. Ziliak. “Food Insecurity Has Economic Root Causes.” Nature Food 3, no. 8 (2022): 567-569.

Harvey, David. “Marx on Income Inequality Under Capitalism.” Global Policy Journal, February 14, 2022. https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/.

Hickel, Jason. The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. London: Heinemann, 2017.

Hope, David, and Julian Limberg. “The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich.” Socio-Economic Review 20, no. 2 (2022): 539-559.

International Monetary Fund. “Sustainable Path to Inclusive Growth in Japan: How to Tackle Income Inequality?” IMF Staff Country Reports 2024, no. 119 (2024): 45-67.

Kela. “Results of Finland’s Basic Income Experiment.” Social Insurance Institution of Finland, 2020.

Kelton, Stephanie. The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. New York: PublicAffairs, 2020.

Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. London: Macmillan, 1936.

Krueger, Anne O. “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society.” American Economic Review 64, no. 3 (1974): 291-303.

Mankiw, N. Gregory. “Defending the One Percent.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2013): 21-34.

Manning, Alan. “The UK National Minimum Wage at Age 22.” Centre for Economic Performance, LSE, 2021.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1. Translated by Ben Fowkes. London: Penguin, 1976 [1867].

Milanovic, Branko. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Naidu, Suresh, and Eric A. Posner. “Labor Monopsony and the Limits of the Law.” Journal of Human Resources 57, no. S (2022): S284-S323.

OECD. “138 Countries and Jurisdictions Agree Historic Milestone to Implement Global Tax Deal.” Press Release, July 2023. https://www.oecd.org/.

———. Income Inequality in the Nordics from a European Perspective. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2024.

———. “The Role and Design of Net Wealth Taxes in the OECD.” OECD Tax Policy Studies No. 26. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018.

Oxfam International. “World’s Top 1% Own More Wealth than 95% of Humanity.” Press Release, September 2024. https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/worlds-top-1-own-more-wealth-95-humanity.

Pareliussen, Jon, et al. “Income Inequality in the Nordics from an OECD Perspective.” Nordic Economic Policy Review 2018. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, 2018.

Patel, Vikram, et al. “Income Inequality and Mental Illness-Related Morbidity and Resilience: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet Psychiatry 4, no. 7 (2017): 554-562.

Pérotin, Virginie. “Worker Cooperatives: Good, Sustainable Jobs in the Community.” Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity 2, no. 2 (2013): 34-47.

Philippon, Thomas, and Ariell Reshef. “Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Finance Industry: 1909–2006.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127, no. 4 (2012): 1551-1609.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Postero, Nancy. The Indigenous State: Race, Politics, and Performance in Plurinational Bolivia. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.

PwC. “Pillar Two Country Tracker.” PwC Global Tax Services, 2024. https://www.pwc.com/.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright, 2017.

Saez, Emmanuel, and Gabriel Zucman. “Progressive Wealth Taxation.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2019, no. 2 (2019): 437-511.

SEED. “Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration: Final Report.” 2021.

Solt, Fredrik. “Economic Inequality and Democratic Political Engagement.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 1 (2008): 48-60.

Statistics Sweden. Wealth Statistics 2023. Stockholm: SCB, 2024.

Steinmayr, Andreas. “Contact versus Exposure: Refugee Presence and Voting for the Far Right.” Review of Economics and Statistics 103, no. 2 (2021): 310-327.

Stewart, Frances. Horizontal Inequalities and Conflict: Understanding Group Violence in Multiethnic Societies. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. The Price of Inequality. New York: Norton, 2012.

Storper, Michael, et al. “Urban Inequalities in the 21st Century Economy.” Applied Geography 117 (2020): 102-188.

Tax Justice Network. “Taxing Extreme Wealth: What Countries Around the World Could Gain from Progressive Wealth Taxes.” Report, December 2023. https://taxjustice.net/.

Thiede, Katherine, and Shannon Monnat. “Income Inequality across the Rural-Urban Continuum in the United States, 1970–2016.” Rural Sociology 86, no. 4 (2021): 899-937.

UNESCO. “The Cycle of Intergenerational Transmission of Education Inequality Can Be Broken.” 2020 GEM Report, 2020. https://gem-report-2020.unesco.org/.

United Nations. “Goal 10: Reduce Inequality Within and Among Countries.” Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024.

———. “Recognizing and Overcoming Inequity in Education.” UN Chronicle, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/.

U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives. “Worker Cooperative Economic Census.” USFWC, 2023.

Vigdor, Jacob, et al. “The Seattle Minimum Wage Study: Final Report.” Evans School of Public Policy, University of Washington, 2022.

White House. “FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces Key Progress on Efforts to Close the Racial Wealth Gap.” April 12, 2024.

Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009.

Wolff, Edward N. “Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962 to 2019.” NBER Working Paper No. 28383 (2021).

World Bank. “Bolsa Família: Brazil’s Quiet Revolution.” Opinion, November 4, 2013. https://www.worldbank.org/.

———. “The Geography of High Inequality: Monitoring the World Bank’s New Indicator.” World Bank Blogs, October 2024. https://blogs.worldbank.org/.

———. “LAC Equity Lab: Income Inequality – Urban/Rural Inequality.” 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/.

———. “WDR 2022 Chapter 1: Introduction – The Economic Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis.” 2022.

World Health Organization. World Report on Social Determinants of Health Equity. Geneva: WHO, 2024.

World Inequality Database. “10 Facts on Global Inequality in 2024.” WID, January 2024. https://wid.world/news-article/10-facts-on-global-inequality-in-2024/.