Introduction: The Luther of Medicine

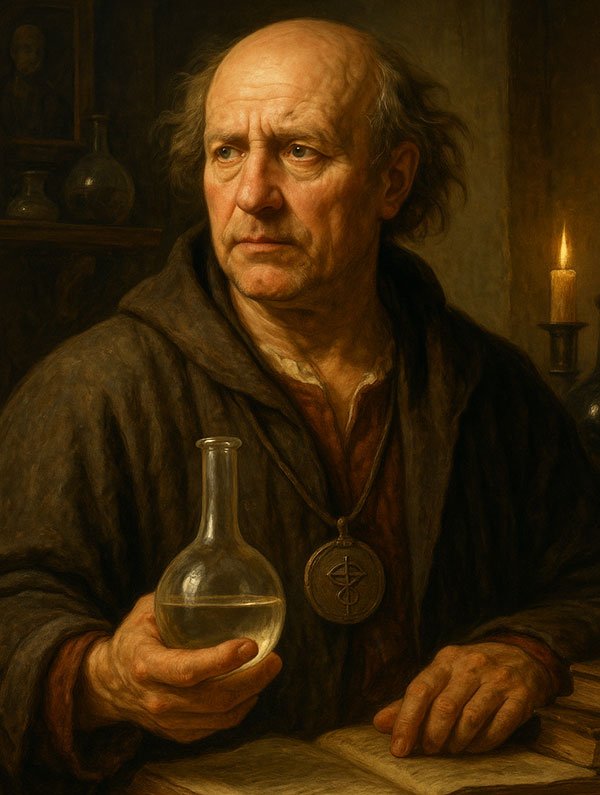

In the tumultuous heart of the European Renaissance, a period of profound upheaval in art, religion, and politics, there strode a figure as brilliant, contradictory, and revolutionary as the age itself. Born Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, he would adopt a name that resonated with both his towering ambition and his radical vision: Paracelsus. To his admirers, he was a prophet of a new science, earning titles that still echo in the halls of medicine and chemistry: the “father of toxicology,” the “founder of medicinal chemistry,” and the “godfather of modern chemotherapy”. To his detractors, he was an arrogant, drunken charlatan, a heretic, and an enfant terrible who delighted in chaos. He was, above all, a polymath who defied easy categorization—a physician, alchemist, natural philosopher, mystic, and lay theologian who straddled the shrinking chasm between a world governed by magic and one defined by empirical science.

The most enduring of his epithets is perhaps the most telling: “the Luther of Medicine”. The comparison is more than a convenient historical parallel. Just as Martin Luther had challenged the centuries-old authority of the Catholic Church, demanding a return to the primary source of scripture, Paracelsus waged a one-man war against the calcified dogmas of ancient medical authorities. He was an “outspoken, heretical, anti-authoritarian freethinker” who saw the academic medicine of his day as a corrupt institution that produced “so many high asses”. His rebellion was not merely intellectual; it was a profound philosophical and even spiritual quest. He sought to tear down the edifice of medicine built on the revered texts of the Greek physician Galen and the Persian polymath Avicenna and to rebuild it on a new foundation: direct, personal experience and the meticulous observation of nature.

Yet, the central paradox of Paracelsus, and the key to understanding his genius, is that his vision of a new science was not a rejection of the esoteric, but its radical reinterpretation. His worldview was a unified whole, where the chemical reactions in a crucible, the movements of the stars, the healing properties of a mountain herb, and the existence of invisible nature spirits were all interconnected parts of a single, divine creation. He did not seek to replace alchemy and astrology with science; he sought to reform them into a new, practical, and Christianized philosophy of nature. He represents a pivotal, liminal moment in Western thought, a bridge between the medieval cosmos and the modern world. To understand Paracelsus is to understand the messy, brilliant, and often contradictory birth of modern science itself—a birth that took place not in a sterile laboratory, but in the fiery crucible of an alchemist who dared to read the “Book of Nature” for himself.

Listen to Our 5-min Deep Dive to get a sense of this article about the life of Paracelsus

Paracelsus The Renegade Alchemist Who Revolutionized Medicine

A World Bound by Ancient Texts: Galen, Avicenna, and Renaissance Medicine

To comprehend the sheer audacity of Paracelsus’s rebellion, one must first understand the intellectual fortress he sought to conquer. The medicine of the early 16th century was not a field of dynamic discovery but one of scholastic preservation, dominated by the colossal authority of two figures: Galen of Pergamum and Avicenna of Persia. For over 1,300 years, their writings were not merely influential; they constituted the very bedrock of medical theory and practice in Europe, their doctrines followed “religiously” by universities and physicians.

The cornerstone of this paradigm was the Galenic doctrine of the four humors, a theory first advanced in the Hippocratic corpus and perfected by Galen in the 2nd century AD. This elegant system posited that the human body contained four essential fluids, or humors: blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Each humor possessed two of the four primary qualities: blood was hot and wet, yellow bile was hot and dry, black bile was cold and dry, and phlegm was cold and wet. Health was defined as the state of perfect balance— eucrasia—among these four humors. Illness, conversely, was a state of imbalance, or dyscrasia, caused by an excess or deficiency of one or more fluids.

This framework was far more than a simple theory of disease; it was a comprehensive cosmology that linked the human body (the microcosm) to the greater universe (the macrocosm). Each humor corresponded to one of the four classical elements, one of the four seasons, a stage of life, and a specific temperament. Blood, aligned with air, spring, and childhood, produced a sanguine (lively, sociable) personality. Yellow bile, linked to fire, summer, and youth, resulted in a choleric (aggressive) temperament. Black bile, corresponding to earth, autumn, and middle age, created melancholy. Phlegm, associated with water, winter, and old age, led to a phlegmatic (apathetic) disposition. Treatment was therefore logical within this system: if illness was an excess of a humor, the cure was to remove it. A fever, considered a sign of excess hot and wet blood, was treated by bloodletting; an overabundance of bile could be addressed with purgatives.

The authority of this system was cemented by the Church, which found Galen’s monotheistic leanings and his belief in a soul compatible with Christian doctrine. For centuries, the Church actively discouraged the dissection of human bodies, meaning that Galen’s own anatomical work, which was foundational, was based almost exclusively on animals like Barbary apes and pigs. This led to demonstrable errors when his findings were applied to human anatomy, yet his authority was so absolute that these flaws went largely unchallenged.

The second pillar of this medical orthodoxy was the Persian philosopher-physician Avicenna (Ibn Sina). His 11th-century masterpiece, Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine), was a monumental five-volume encyclopedia that synthesized the medical knowledge of the Greco-Roman world with the advancements of Islamic and Persian scholars. The Canon was a model of systematic organization and logical clarity, covering everything from anatomy and physiology to pharmacology and the clinical diagnosis of diseases. Translated into Latin in the 12th century, it became the definitive medical textbook in European universities, with institutions from Bologna and Montpellier to Krakow making it the core of their curriculum well into the 17th century.

The combined weight of Galen’s philosophy and Avicenna’s systematic codification created a powerful, self-contained, and intellectually satisfying paradigm. Its great strength was its comprehensiveness; it had an answer for everything. But this was also its fatal flaw. It fostered a medical culture where the primary act of a physician was not to observe the patient before them, but to consult the ancient texts and fit the patient’s symptoms into the pre-existing theoretical framework. Knowledge was derived from scholastic interpretation, not empirical investigation. It was this bookish, authoritative, and text-bound world that Paracelsus was born into—and the world he was determined to set on fire.

The Life of a Rebel: The Peregrinations of Theophrastus von Hohenheim

The life of Paracelsus was a relentless journey, a constant state of motion and conflict that directly forged his revolutionary philosophy. His experiences as a perpetual outsider, learning from the world rather than from the cloistered halls of academia, became the raw material for his assault on the medical establishment.

Formative Years (1493-c.1515)

Born Theophrastus Bombast of Hohenheim in 1493, near the Swiss town of Einsiedeln, his very origins set him apart. His father, Wilhelm, was an impoverished physician and an illegitimate son of a noble Swabian family; his mother was a bondswoman at a local abbey, meaning Paracelsus inherited her lower social status. This position as an outsider, neither fully noble nor fully common, would define his life. He received his earliest education from his father, who taught him the fundamentals of medicine, surgery, and, crucially, alchemy.

A pivotal move came in 1502 when the family relocated to Villach in Austria, a major mining center controlled by the wealthy Fugger family. Here, the young Paracelsus gained an education no university could offer. He worked in the mines and smelting laboratories, acquiring firsthand, practical knowledge of metallurgy, the properties of metals, and the occupational diseases that afflicted miners—observations that would later lead to his groundbreaking work on toxicology. He also studied under the tutelage of several clergymen, most notably the learned abbot Johannes Trithemius, a renowned practitioner of alchemy, astrology, and magic, who undoubtedly deepened his interest in the esoteric arts.

The Wandering Scholar (c.1515-1526)

After obtaining a baccalaureate in medicine from the University of Vienna around 1510 and likely a doctorate from the University of Ferrara in Italy around 1515, Paracelsus embarked on the peripatetic life that would become his hallmark. He traveled throughout Europe and reportedly into the Middle East, attending a string of prestigious universities—Basel, Tübingen, Wittenberg, Cologne—only to be bitterly disappointed by them all. He famously scoffed at their scholasticism, wondering how “the high colleges managed to produce so many high asses”.

He came to believe that true knowledge was not found in books but in experience. “A doctor must be a traveller,” he declared, for “Knowledge is experience”. He turned his back on the Latin-speaking elite and sought wisdom from the people and places they disdained. He learned from barber-surgeons, executioners, midwives, gypsies, and even “old robbers, and such outlaws,” believing their practical, hard-won knowledge held more truth than the dry theories of the ancients. His travels also saw him serve as an army surgeon in the brutal wars sweeping across the Netherlands, Italy, and Scandinavia. On the battlefield, he was confronted with the gruesome reality of wounds, an experience that gave him a profound belief in interventional medicine and the simple, natural healing power of the body—a stark contrast to the passive, regimen-based approach of Galenic physicians.

The Basel Firestorm (1527-1528)

The climax of his career, and the moment of his most dramatic confrontation with the establishment, came in 1527. Having gained fame for successfully treating the leg of the celebrated Basel printer Johann Froben, saving it from amputation, he was appointed town physician and professor at the University of Basel. He wasted no time in igniting a firestorm of controversy.

He shattered centuries of academic tradition by choosing to lecture not in the scholarly Latin, but in the German vernacular, making his teachings accessible to a wider audience beyond the university elite. He posted advertisements for his lectures inviting not just students, but the general public, a move that infuriated the closed-off faculty. He openly derided his colleagues and their worthless remedies, earning their immediate and lasting enmity.

The point of no return came on St. John’s Day, June 24, 1527. In a moment of supreme theatrical defiance, timed for a day long associated with midsummer bonfires and purification, Paracelsus stood before the university and publicly burned the canonical works of Galen and Avicenna in a brass pot filled with sulfur and nitrate. This was no mere fit of rage; it was a carefully staged philosophical statement, a public declaration that the age of textual authority was over. “Reading never makes a physician,” he proclaimed. “Medicine is an art and requires practical experience”. The act was a physical manifestation of his core belief: the “Book of Nature” was the only true text, and the wisdom of the ancients was nothing but ash. This ultimate act of iconoclasm, coupled with his abrasive personality and a dispute over a fee, sealed his fate. By 1528, with his powerful patron Froben now dead, Paracelsus was forced to flee Basel, exiled and reviled by the very establishment he had sought to reform.

Final Years (1528-1541)

The remainder of his life was a return to wandering. He roamed through Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, often impoverished and always in conflict, yet it was during this period that he produced his most important writings. He composed his great philosophical manifestos, the Paragranum (1530) and the Opus Paramirum (1531), which laid out the “four pillars” of his new medicine. In 1536, he published Die Große Wundarzney (The Great Surgery Book), a work based on his battlefield experience that became his most successful publication and helped restore some of his tarnished reputation.

He died in Salzburg in 1541 at the age of 47, his death shrouded in mystery. While some accounts claim he was thrown down a flight of stairs by thugs hired by his medical enemies, a 20th-century chemical analysis of his exhumed remains revealed extremely high levels of mercury, suggesting he may have succumbed to chronic poisoning—perhaps a victim of the very potent mineral remedies he championed. His life, like his work, ended in controversy, a testament to the turbulent path of a man who lived and died as a revolutionary.

Tearing Down the Pillars: Paracelsus’s New Philosophy of Disease

Paracelsus’s revolution was not merely a matter of burning books; it required the construction of an entirely new intellectual framework for understanding health and illness. He did not just critique the Galenic system; he dismantled it at its foundations and replaced it with a radical philosophy that, while couched in the language of alchemy and mysticism, contained the conceptual seeds of modern medicine.

His first and most fundamental break was the complete rejection of humoralism. The notion that disease was a simple internal imbalance of four bodily fluids was, to him, an absurdity that flew in the face of observation. In its place, he proposed two profoundly modern concepts that would change the course of medical history.

First, he argued for the external causation of disease. Illness, he maintained, was not generated from within the body but was caused by specific, hostile agents from the outside world that invaded the body’s systems. These were not abstract imbalances but distinct entities, “poisons” or “acrimonies” that originated in the environment. His experience in the mines provided the perfect example: he argued that the “miners’ disease” (silicosis) was not a punishment from mountain spirits, as was commonly believed, but the direct result of inhaling metallic vapors. This shift from an internal to an external cause was monumental. It transformed disease from a state of being into an event—an attack by a foreign enemy.

Second, Paracelsus introduced the concept of localization. He argued that these external agents did not cause a vague, systemic imbalance but instead targeted and settled in a specific organ or part of the body. A disease of the lungs was a disease in the lungs, caused by a poison that had lodged there. This was a direct precursor to the modern concept of the “target organ of toxicity,” a cornerstone of pathology and toxicology. Together, these two ideas—external cause and specific location—created the very notion of a “disease entity.” No longer was there just one problem (imbalance) with different manifestations; there were now hundreds of distinct diseases, each with its own specific cause, its own location in the body, and, logically, its own specific cure. This was the philosophical paradigm shift that made the search for a “magic bullet” drug possible centuries later.

To replace the four classical elements of earth, air, fire, and water, Paracelsus posited his own alchemical trinity, the tria prima. He believed that all matter, from a star to a human liver, was composed of three essential principles: Sulfur, the principle of inflammability, soul, and character; Mercury, the principle of liquidity, fusibility, and spirit; and Salt, the principle of stability, incombustibility, and the physical body. When a piece of wood burns, he explained, the flame is its Sulfur, the smoke its Mercury, and the ash its Salt. Health was the harmonious union of these three principles in the body. Disease was their separation or discord, caused by an external poison.

This entire system was bound together by the ancient Hermetic principle of correspondence: “As above, so below.” Paracelsus saw man as a microcosm, a universe in miniature that perfectly reflected the great universe, the macrocosm. “Heaven is man and man is heaven,” he wrote. This meant that the forces at work in the stars, the earth, and the elements were the same forces at work within the human body. Therefore, to be a true physician, one had to be more than a mere technician. One must be a philosopher to understand the nature of things, an astronomer to understand the celestial influences on the body’s chemistry, and, most importantly, an alchemist to understand and manipulate the fundamental building blocks of life itself.

The Alchemist’s Cure: Iatrochemistry and the Birth of Toxicology

The practical application of Paracelsus’s new philosophy was iatrochemistry, a field he single-handedly created. Derived from the Greek iatros (physician), iatrochemistry was the fusion of alchemy and medicine, a revolutionary new science that viewed the human body as a chemical laboratory and disease as a chemical problem requiring a chemical solution. Paracelsus declared that the true and noble purpose of alchemy was not the foolish pursuit of making gold, but the divine mission of preparing powerful medicines, or arcana, to heal the sick.

This led him to radically overhaul the pharmacy of his day. He scorned the Galenists’ reliance on complex herbal mixtures, which he felt often lacked the potency to combat serious disease. Instead, he championed the use of powerful, chemically prepared remedies derived from the mineral kingdom. He introduced inorganic salts, metals, and minerals into the pharmacopeia, advocating for the careful use of substances like mercury, lead, antimony, copper sulfate, and zinc, a metal he is credited with naming. He developed a clinical description of syphilis, arguing it could be successfully treated with carefully measured internal doses of mercury compounds, a stark contrast to the ineffective guaiac wood treatment then in vogue. Perhaps his most famous and enduring preparation was laudanum, an alcoholic tincture of opium he developed as a potent and effective painkiller, which he was rumored to carry in the pommel of his longsword.

The use of such potent and obviously toxic substances was met with horror by the established medical community. This is where Paracelsus introduced his most important and lasting contribution to science, a principle that forms the bedrock of modern toxicology and pharmacology: the dose-response relationship. His dictum, now famously condensed to “the dose makes the poison,” was originally articulated as: “Alle Ding sind Gift und nichts ohn’ Gift; allein die Dosis macht, das ein Ding kein Gift ist“—”All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison”.

This was not just a clever aphorism; it was a profound conceptual breakthrough. Paracelsus recognized that toxicity is not an inherent and absolute quality of a substance but a relative one, entirely dependent on the quantity administered. A substance that is a deadly poison at a high dose can be a harmless—or even beneficial—remedy at a low dose. This single principle provided the intellectual framework that made his entire chemical pharmacy coherent and defensible. It resolved the apparent paradox of using poisons to heal. It allowed for the critical distinction between a substance’s hazard (its intrinsic capacity to cause harm) and its risk (the probability of that harm occurring at a specific level of exposure), a distinction that remains fundamental to all toxicological assessment and government regulation today.

This concept was intertwined with his belief in the principle of similitude, or “like cures like” (similia similibus curantur). He argued that a disease caused by a specific poison in the macrocosm could be cured by administering a tiny, controlled dose of that same or a similar poison, which would act to neutralize its counterpart in the body. This idea, which anticipated the principles of modern homeopathy, was another expression of his belief in a universe bound by sympathies and correspondences. By redirecting the alchemist’s arts of distillation and purification—what he called the “spagyric” art—away from gold and toward medicine, Paracelsus transformed the ancient craft, laying the practical and philosophical groundwork for the modern science of pharmacology.

Reading the Book of Nature: Herbalism and the Doctrine of Signatures

While Paracelsus is famed for introducing chemical remedies, he did not abandon the plant kingdom. Rather, he approached it with the same revolutionary spirit, seeking knowledge not from the dusty herbals of the ancients but from direct communion with the “Book of Nature”. For Paracelsus, nature was the greatest school of all, a living text authored by God, and “all things belonging to Nature exist for the sake of Man”. The key to reading this divine text was a concept he popularized and integrated deeply into his philosophy: the Doctrine of Signatures.

The doctrine, which has ancient roots but was systematized and championed by Paracelsus, holds that God, in His benevolence, placed a “signature” on every plant, a visible clue to its hidden medicinal purpose. This signature was a physical resemblance—in shape, color, habitat, or other quality—to the human body part or the disease it was intended to heal. This was another manifestation of the “like cures like” principle. To practice medicine was to learn how to decipher these divine symbols. His influential work De Natura Rerum (On the Nature of Things) contains one of his most important expositions on this theory.

This approach reveals that Paracelsus’s empiricism was not the cold, objective observation of a modern scientist. It was a form of hermeneutics—the theological art of interpretation. He was not merely cataloging flora; he was engaging in a mystical exegesis of God’s creation. The universe, in his view, was fundamentally meaningful, communicative, and benevolent, with cures deliberately signposted for those with the wisdom to see them. This worldview elegantly reconciles his advocacy for both potent mineral drugs and herbal remedies. Both were discovered by reading the Book of Nature—one by using the alchemist’s fire to reveal its hidden chemical essence (arcanum), the other by using the physician’s eye to read its visible, God-given form.

The following table illustrates the logic of the Doctrine of Signatures with several well-known examples:

| Plant | Signature (Appearance/Quality) | Purported Medicinal Use (According to the Doctrine) | Source(s) |

| Walnut | Resembles a human brain, with hemispheres and folds. | Curing head ailments, madness, and strengthening the brain. | |

| Hepatica (Liverwort) | The three-lobed leaves resemble the lobes of the human liver. | Treating liver disorders. | |

| Lungwort | The spotted leaves resemble diseased lung tissue. | Curing pulmonary ailments like bronchitis and asthma. | |

| Eyebright | The flower’s pattern resembles a human eye. | Treating eye infections and conditions like cataracts. | |

| Ginseng | The root resembles a human figure (“man-root”). | A panacea, or cure-all, to strengthen the entire body. | |

| Bloodroot | The roots exude a scarlet-red sap. | Treating diseases of the blood and circulatory system. | |

| Willow | Grows in damp environments. | Treating rheumatic conditions, which were often aggravated by dampness. |

Beyond the Veil of Nature: The World of Elementals

The most esoteric and, to the modern mind, fantastical aspect of Paracelsus’s thought is his detailed and systematic cosmology of nature spirits, or “elementals.” For Paracelsus, this was not folklore or poetic metaphor; it was a serious philosophical and theological investigation, a necessary component of his quest to map the entirety of God’s creation, both visible and invisible. In his posthumously published work,

A Book on Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies, and Salamanders, and on the Other Spirits (1566), he sought to bring these beings “outside the cognizance of the light of nature” into a rational, ordered system.

He argued that just as the visible world is populated by countless creatures, so too is the invisible spiritual counterpart of nature inhabited by its own host of beings. He classified these elementals into four distinct categories, each corresponding to one of the four classical elements which they inhabit as their natural “chaos,” or environment :

- Gnomes (or Pygmies) are the beings of Earth. Described as short, they can move through solid rock, soil, and walls as effortlessly as a human moves through air. They are the guardians of the earth’s hidden treasures.

- Undines (or Nymphs) are the beings of Water. Similar in size to humans, they inhabit forest pools, waterfalls, and the depths of the seas. Paracelsus noted their beautiful singing voices could sometimes be heard over the sound of water.

- Sylphs are the beings of Air. Taller, stronger, and coarser than humans, they are the closest to humanity in his conception because they move through the same medium. However, they burn in fire, drown in water, and become trapped in earth.

- Salamanders are the beings of Fire. Described as long, lean, and narrow, they are the spirits of fire itself, living within flames as their natural habitat.

Crucially, Paracelsus insisted that these beings were not pure spirits like angels or demons. They were physical creatures, an intermediate order of life between humanity and the spiritual realms. They have “flesh, blood and bones,” they eat, sleep, talk, and reproduce like humans. The fundamental difference, and the source of their unique ontological status, is that elementals lack an immortal, divine soul. A human, according to Paracelsus’s Christian framework, is composed of a mortal elemental body, a mortal sidereal spirit (from the stars), and an immortal soul, which is the “breath of God”. Elementals possess the first two components but lack the third. At death, they do not face judgment or eternal life; they simply disintegrate back into the element from which they came.

In a famous and influential assertion, however, he claimed that there was one way for an elemental to transcend its nature: an Undine could acquire an immortal soul by marrying a human and bearing their child. This idea, blending natural philosophy with romance and theology, would echo through centuries of folklore and literature, most famously in Hans Christian Andersen’s

The Little Mermaid.

For Paracelsus, this study was a vital theological endeavor. These beings were among the “marvelous works” of God, part of the rich tapestry of creation. He argued that the Church had wrongly conflated these natural, soulless creatures with devils. To disbelieve in them, he contended, was a failure of faith, a refusal to accept the full scope of God’s power. To doubt the unseen creatures of nature, he reasoned, was akin to doubting the unseen miracles of Christ. His work on elementals was therefore not a flight of fancy but a logical and necessary part of his grand project: to construct a unified, Christian-Neoplatonic cosmology that accounted for every aspect of the universe, leaving no part of God’s creation unexamined or unexplained.

Conclusion: The Enduring, Controversial Legacy of Paracelsus

To assess the legacy of Paracelsus is to embrace paradox. He remains one of the most contentious and enigmatic figures in the history of science, a man whose work was simultaneously backward-looking and breathtakingly forward-thinking. He is remembered as both a scientific pioneer and a purveyor of occultism, a rationalist who championed experimentation and a mystic who believed in a world animated by invisible forces. Most of his writings were not even published in his lifetime, yet his influence, growing posthumously through the efforts of his followers, the “Paracelsians,” sparked controversies that raged for over a century.

His concrete contributions were foundational. He is rightly called the “father of toxicology” for his revolutionary principle that the dose alone makes the poison, a concept that underpins all modern pharmacology. He created iatrochemistry, forcing medicine to engage with the chemical nature of the body and paving the way for chemotherapy. He introduced concepts that are now axiomatic in medicine: that diseases are specific entities with external causes, that they localize in target organs, and that some illnesses are occupational hazards tied to environmental exposure. He advocated for humane treatment of the mentally ill, viewing their conditions as diseases rather than demonic possessions.

Yet, for every idea that feels modern, there is another steeped in the magical worldview of the 16th century. His chemistry was the alchemy of the tria prima, his astronomy was the astrology of the macrocosm’s influence on the microcosm, and his natural history included a detailed taxonomy of gnomes and sylphs.

Ultimately, the greatest legacy of Paracelsus was not any single discovery, but a fundamental and irreversible shift in the scientific mindset. His true revolution was epistemological. By publicly burning the works of Galen and Avicenna, he symbolically destroyed the notion that truth is a static inheritance, found only in the revered texts of the past. He replaced the authority of the book with the authority of experience, demanding that physicians look away from the page and toward the patient, away from the university and toward the vast, living laboratory of nature.

Many of his own theories were, by modern standards, incorrect. But as one biographer aptly noted, he was “wrong and reasonable”. The method he championed—observation, experimentation, a willingness to challenge all authority—was profoundly and lastingly correct. He created the intellectual and cultural space for empirical inquiry to flourish, allowing future generations to build upon his work even as they discarded his more fantastical conclusions. Paracelsus was a man of his time, a modern thinker attempting to map a medieval cosmos. In the process of trying to understand that world of magic, alchemy, and divine signatures, he inadvertently drew the first, messy, but essential sketches of our own.

References

Ackerknecht, E. H. 1982. A Short History of Medicine. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ball, Phillip. 2006. The Devil’s Doctor: Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance Magic and Science. London: William Heinemann.

Borzelleca, Joseph F. 2000. “Paracelsus: Herald of Modern Toxicology.” Toxicological Sciences 53, no. 1 (January): 2–4.

Clendening, L. 1960. Source Book of Medical History. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Debus, Allen G. 1999. “Paracelsus and the Medical Revolution of the Renaissance; A 500th Anniversary Celebration.” In Paracelsus, Five Hundred Years; Three American Exhibits. Washington, DC: National Library of Medicine.

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas, ed. 1999. Paracelsus: Essential Readings. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Jargin, Sergei V. 2017. “The Doctrine of Signatures in the Light of Modern Science.” Hektoen International: A Journal of Medical Humanities, June 17, 2024.

Karpen, K. O., and K. K. Klee. 2017. “Paracelsus: Father of Toxicology.” Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, University of Iowa. October 23, 2017.

Michaleas, Spyros N., Konstantinos Laios, Gregory Tsoucalas, and Georges Androutsos. 2021. “Theophrastus Bombastus Von Hohenheim (Paracelsus) (1493–1541): The Eminent Physician and Pioneer of Toxicology.” Folia Medica 63, no. 5: 767–73.

Pagel, Walter. 1982. Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance. 2nd ed. Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

Papanikolaou, E. 2022. “The Conceptual Shifts in Paracelsus’s Matter Theory.” Athens Journal of History 8, no. 1: 57-74.

Shackelford, Jole. 2020. “Bruce T. Moran, Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life.” Social History of Medicine 33, no. 4 (November): 1381–82.

Stoddart, Anna M. 1911. The Life of Paracelsus, Theophrastus von Hohenheim, 1493-1541. London: J. Murray.

Temkin, C. Lilian, George Rosen, Gregory Zilboorg, and Henry E. Sigerist, trans. 1941. Four Treatises of Theophrastus von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Touwaide, A. 2012. “Paracelsus.” In Art & Science of Healing: From Antiquity to the Renaissance. Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan.

Vries, Lyke de, and Leen Spruit. 2017. “Paracelsus and Roman censorship: Johannes Faber’s 1616 report in context.” Intellectual History Review 28, no. 2: 225-254.

Waite, Arthur Edward, ed. and trans. 1894. The Hermetic and Alchemical Writings of Aureolus Philippus Theophrastus Bombast, of Hohenheim, called Paracelsus the Great. 2 vols. London: J. Elliott and Co.

Weeks, Andrew, ed. and trans. 2008. Paracelsus: Essential Theoretical Writings. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Suggested Further Reading

For those wishing to delve deeper into the complex world of Paracelsus, the following works offer authoritative and accessible entry points:

- Pagel, Walter. Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance. 2nd ed. Karger, 1982. Considered the definitive scholarly biography by the foremost 20th-century authority on Paracelsus. It is a dense but indispensable work for understanding the philosophical underpinnings of his medicine.

- Moran, Bruce T. Paracelsus: An Alchemical Life. Reaktion Books, 2019. A more recent and highly readable biography that masterfully combines scholarly rigor with a compelling narrative. Moran artfully places Paracelsus within the social, religious, and alchemical context of his time, making him accessible to both specialists and general readers.

- Weeks, Andrew, ed. and trans. Paracelsus: Essential Theoretical Writings. Brill, 2008. A landmark achievement in Paracelsian scholarship, this volume provides new, reliable, and critically annotated English translations of some of his most important works, including Paragranum and Opus Paramirum. It is the best resource for engaging directly with Paracelsus’s own complex prose.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas, ed. Paracelsus: Essential Readings. North Atlantic Books, 1999. An excellent anthology of translated excerpts from a wide range of Paracelsus’s writings, organized thematically. It serves as a valuable and accessible introduction for students and those new to his work.

- Debus, Allen G. The English Paracelsians. Franklin Watts, 1965. A classic study in the history of science that traces the profound and controversial influence of Paracelsus’s ideas in England, demonstrating the long-lasting impact of the movement he inspired.

- Temkin, C. Lilian, et al., trans. Four Treatises of Theophrastus von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus. The Johns Hopkins Press, 1941. An older but still valuable collection that provides English translations of four key texts, including his groundbreaking work on miners’ occupational diseases and his famous book on elementals, offering a direct glimpse into the breadth of his interests.