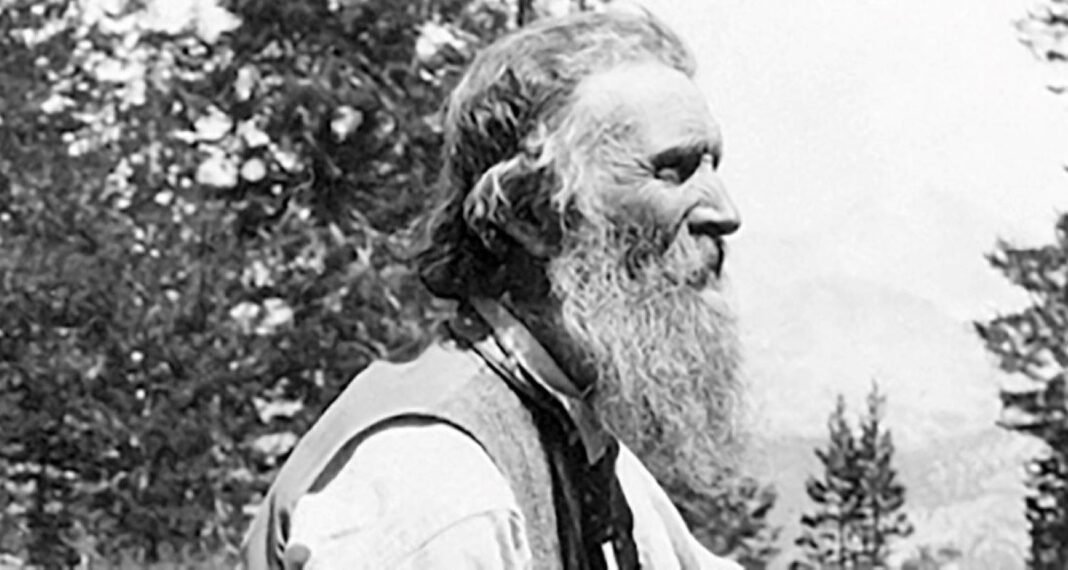

John Muir (1838-1914) stands as a monumental figure in the American consciousness, a presence as towering and enduring as the granite cliffs of Yosemite he so loved. He is remembered as a naturalist, writer, inventor, and activist, but his most resonant title is the “Father of the National Parks”. His work is foundational to the modern environmental movement, yet his legacy, once revered without question, is now undergoing a necessary and complex re-evaluation. Muir was more than a conservationist; he was a prophet who articulated a new American gospel of the wild, one that continues to shape how the nation perceives its relationship with the natural world.

This report argues that John Muir’s profound impact stems from his unique ability to fuse a scientific eye with a prophetic voice, creating a powerful and persuasive philosophy of nature. However, this philosophy, rooted in a romanticized vision of “unpeopled wilderness,” contained inherent contradictions and harmful racial biases that the modern environmental movement is only now beginning to fully confront. To understand Muir is to grapple with the sublime beauty of his vision and the troubling shadows of his legacy, recognizing a figure whose work is both an inspiration and a challenge.

Listen to our Deep Dive -John Muir: Unearthing the Complex Legacy of the Father of the National Parks

Part I: The Forging of a Naturalist (1838-1867)

From Dunbar to the Wisconsin Wilderness

John Muir’s journey began not in the sun-drenched valleys of California but in the coastal town of Dunbar, Scotland, where he was born in 1838. His early life was dominated by his father, Daniel Muir, a stern grain merchant and fundamentalist Presbyterian who governed his household with severe piety. The elder Muir worshipped a “God of wrath” and enforced a punishing regimen of labor and religious instruction, most notably demanding that his children memorize vast portions of the Bible. In 1849, when John was eleven, the family emigrated to the United States, carving a farm out of the Wisconsin frontier.

This upbringing was the crucible in which Muir’s worldview was forged. The austerity of his father’s Calvinism created a spiritual void that the vibrant, seemingly benevolent natural world of Wisconsin rushed to fill. While his father saw evil in most childish activities, Muir found freedom and wonder exploring the woods, bogs, and meadows surrounding the farm. His voracious reading and self-directed education in botany, geology, and mechanics, often conducted in stolen moments at night, became acts of intellectual and spiritual rebellion against his father’s rigid authority. He briefly attended the University of Wisconsin, excelling in subjects that interested him but ultimately leaving without a degree, finding the “outdoor laboratory of nature” a more compelling classroom than any formal institution.

The severe religious indoctrination of his youth did not disappear; instead, it provided the very architecture for his later environmental theology. The Bible, forced upon him by his father, was conceptually replaced by the “Book of Nature”. The framework of scripture, revelation, sin (the destruction of nature), and salvation (preservation) was transposed onto the natural world. He would later find his “cathedral” in the wilderness and preach a “gospel of conservation,” styling himself as a “John the Baptist” whose duty was to immerse humanity in a “mountain baptism”. In this way, his father’s harshness paradoxically equipped him with the language and zeal of a prophet.

An Epiphany in Darkness

Before dedicating his life to nature, Muir pursued a promising career as an inventor. His mechanical ingenuity was remarkable; at the University of Wisconsin, he created fantastic devices like a clock that could light a lamp and a bed that would tip its occupant onto the floor at a set time. After leaving college, he found success working in factories in Canada and later in Indianapolis, Indiana, where he was employed at a carriage parts shop. His path seemed set toward a life in mechanics and industry.

This trajectory was shattered on March 6, 1867. While working on a machine, a sharp file he was using slipped, flew up, and pierced his right cornea. The trauma was so severe that his left eye went blind in sympathy, plunging him into a world of darkness. Confined to a darkened room for six weeks, he faced the terrifying possibility of permanent blindness. In his despair, he cried out, “My right eye is gone, closed forever on all God’s beauty”.

This event became the pivotal turning point of his life, a “dark night of the soul” that forced an internal reckoning. The potential loss of sight made the visual splendor of the world infinitely precious. When his vision gradually returned, he experienced a profound conversion. The accident was not merely a misfortune but a divine lesson. “God has to nearly kill us sometimes, to teach us lessons,” he later reflected. He made a conscious, life-altering decision to abandon his former path. As he wrote, “I bade adieu to all my mechanical inventions, determined to devote the rest of my life to the study of the inventions of God”. The accident transformed him from a man working on machines to a man dedicated to deciphering the “divine manuscript” of the wild, setting the course for all his future work.

Part II: The Gospel of the Wild (1867-1892)

A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf

Newly consecrated to his life’s purpose, Muir immediately embarked on his first great pilgrimage. In September 1867, he began a 1,000-mile walk from Indiana to the Gulf of Mexico, a journey he chronicled in a journal that would be published posthumously. This trek was his formal matriculation into what he called the “University of the Wilderness”. The journal from this walk is a foundational text of American environmentalism, revealing the genesis of his biocentric and anti-anthropocentric worldview.

During his journey, Muir began to radically question the prevailing Judeo-Christian premise of human dominion over nature. “The world, we are told, was made especially for man,” he mused, “— a presumption not supported by all the facts”. He extended a sense of divine belonging and kinship to creatures often reviled, observing alligators in a Florida swamp and concluding they “are part of God’s family, unfallen, un-depraved and cared for with the same species of tenderness and love as is bestowed on angels in heaven”. This view, that all creatures are “earth-born companions and our fellow mortals,” was revolutionary for its time.

However, a critical and revealing tension emerges in these same journal entries. While Muir was developing a profound empathy for non-human life, his writings display a shocking lack of it for many of the people he encountered. His descriptions of African Americans in the post-Civil War South are laced with the era’s most vicious stereotypes. He uses the derogatory term “Sambos” to describe them as lazy and expresses fear of “idle negroes” he saw “prowling about everywhere”. Similarly, he described the Indigenous people he met as “dirty” and appearing to have “no right place in the landscape”. This stark contradiction reveals that from the very beginning, his expansive and sacred vision of “nature” was built upon a troubling and exclusionary racial hierarchy. His circle of “fellow mortals” did not, at this stage, fully and equally include all humans, a blind spot that would profoundly complicate his legacy.

The Range of Light: Finding a Home in the Sierra

After his walk to the Gulf and a brief trip to Cuba, where he contracted malaria, Muir abandoned his plan to travel to South America and instead sailed to California, arriving in San Francisco in March 1868. When asked where he wanted to go, he famously replied, “To any place that is wild”. He soon made his way to the Sierra Nevada, the mountain range that would become his spiritual home and the heart of his life’s work.

He spent the next several years living in the Yosemite Valley, working as a shepherd and a sawmill operator, but dedicating every possible moment to exploring the high country. He called the Sierra the “Range of Light,” and his writings from this period are filled with an ecstatic, almost mystical reverence for its grandeur. “We are now in the mountains and they are in us,” he wrote in his journal, “kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us”. The Sierra was not just a place of study; it was his sanctuary, his laboratory, and his cathedral. It was here that he developed his then-radical geological theory that the spectacular formations of Yosemite Valley were not the result of a cataclysmic earthquake, as was widely believed, but had been slowly and patiently carved by massive glaciers over millennia. This work, grounded in careful observation, established his scientific credibility and gave his passionate advocacy a foundation of empirical authority that his detractors could not easily dismiss.

The Voice of the Wilderness: Muir’s Literary Awakening

During his time in Yosemite, Muir’s fame as a guide and naturalist grew, and he hosted distinguished visitors including Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Harvard botanist Asa Gray, and the scientist Joseph LeConte. Encouraged by friends, particularly his mentor Jeanne Carr, Muir began to translate his experiences and philosophies into articles for a national audience. His work appeared in popular and respected periodicals like Overland Monthly, Harper’s, and The Century Magazine, bringing the wonders of the Sierra to readers across the country. His major books, including The Mountains of California (1894), Our National Parks (1901), and The Yosemite (1912), would cement his reputation as America’s preeminent nature writer.

Muir’s literary style is his most powerful and enduring tool. He masterfully blended meticulous scientific observation with lyrical, quasi-religious prose, creating a voice that was both authoritative and deeply moving. He personified nature, describing winds creating a “passionate music” and trees “chanting and bowing low as if in worship”. This was a deliberate evangelistic strategy. “I care to live only to entice people to look at Nature’s loveliness,” he confessed to Carr, expressing his desire “to baptize all of mine in the beauty of God’s mountains”. He was not merely a writer; he was a missionary for the wild, using his pen to convert a nation to what he called the “gospel of conservation”.

In doing so, Muir’s work represents a pivotal evolution of American Transcendentalism. He revered Emerson and Thoreau and was deeply influenced by their philosophy, but he moved their ideas from the intellectual realm of the study to the visceral reality of the summit. When Emerson visited Yosemite, Muir was deeply disappointed that the elder philosopher, constrained by age and convention, refused to camp out with him under the sequoias, seeing it as a failure of Transcendentalism to fully commit to its own ideals. For Muir, faith in nature had to be embodied, physical, and experiential. His legacy is thus not just in the lands he helped preserve, but in the creation of a uniquely American literary tradition where adventure, science, and spirituality are inextricably linked.

Part III: The Political Wilderness: Advocacy and Alliances (1892-1914)

An Unlikely Friendship: Muir and Roosevelt in Yosemite

By the turn of the century, Muir’s writings had captured the attention of the nation’s most powerful reader: President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1903, Roosevelt traveled to California and invited Muir to guide him through Yosemite. For three days, the president and the naturalist camped together in the high country, largely shedding the entourage of reporters and staff. They discussed conservation around the campfire, with Muir, the passionate preservationist, making his case directly to the president.

This was arguably the most consequential camping trip in American history. Muir used the time to impress upon Roosevelt the spiritual and intrinsic value of wilderness, pushing him beyond his more utilitarian “conservationist” leanings which focused on the sustained-yield management of resources. The trip had a direct and massive impact. Roosevelt returned to Washington newly invigorated, and over the course of his presidency, he would go on to protect some 230 million acres of public land, an area larger than the state of Texas. This included the establishment of five national parks, 18 national monuments, 51 federal bird reserves, and 150 national forests. Muir’s influence was particularly crucial in the 1906 federal action that finally returned Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove, which had been managed by the state of California, to become part of a unified and federally protected Yosemite National Park. The trip demonstrated that Muir was not simply a wandering mystic but also a shrewd political operator who understood the power of personal influence. It cemented the idea of wilderness preservation as a national, patriotic duty, linking it to the American identity of ruggedness and natural grandeur that Roosevelt himself embodied.

The Great Debate: Preservation vs. Conservation

Muir’s political work inevitably brought him into conflict with another giant of the era, Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Their differing philosophies represent the foundational ideological schism of the American environmental movement, a clash between ecocentric and anthropocentric worldviews that continues to shape policy today.

Muir was the champion of preservation. He believed that nature possessed an intrinsic, spiritual value and should be protected from human interference in a pristine state. Wilderness was a temple to be revered, a source of healing and spiritual renewal. Pinchot, in contrast, was the architect of conservation. A professional forester educated in Europe, he advocated for the scientific and sustainable management of natural resources for human benefit. His guiding principle was utilitarian: “the greatest good for the greatest number for the longest time”. For Pinchot, forests were resources to be managed wisely, not locked away.

This philosophical divide led to the creation of America’s dual system of federal land management. Muir’s preservationist ethos is the guiding spirit of the National Park Service, created in 1916 with a mandate to leave its lands “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations”. Pinchot’s conservationist doctrine is the foundation of the U.S. Forest Service, which manages its lands for multiple uses, including recreation, but also logging, mining, and grazing. While they are often portrayed as bitter enemies, particularly over the Hetch Hetchy controversy, Muir and Pinchot were initially friends and allies who worked together on the National Forest Commission of 1896, and their competing visions ultimately created the complementary, if sometimes conflicting, land management system that exists today.

| Feature | John Muir (Preservation) | Gifford Pinchot (Conservation) |

| Core Philosophy | Ecocentric: Nature has intrinsic, spiritual value, independent of humans. | Anthropocentric/Utilitarian: Natural resources should be managed for human benefit. |

| View of Nature | A sacred temple, a divine manuscript, a source of spiritual renewal and healing. | A collection of natural resources (timber, water, minerals) to be used wisely and scientifically. |

| Primary Goal | Preserve wilderness in its pristine, untouched state for aesthetic and spiritual reasons. | Ensure the “greatest good for the greatest number for the longest time” through sustainable use. |

| Stance on Use | Opposed commercial exploitation; land should be for recreation, study, and spiritual uplift. | Supported sustainable, regulated use by industry (logging, mining, grazing) under scientific management. |

| Key Battleground | Hetch Hetchy Valley. | Hetch Hetchy Valley. |

| Resulting Agency | National Park Service (ethos). | U.S. Forest Service (ethos). |

The Soul of the Mountains: The Battle for Hetch Hetchy

The philosophical conflict between Muir and Pinchot erupted into a full-blown national political battle over the fate of the Hetch Hetchy Valley. A stunning glacial valley within the boundaries of Yosemite National Park, Hetch Hetchy was identified by the city of San Francisco as an ideal location for a reservoir to provide a stable supply of water and electricity, a need made urgent by the devastating 1906 earthquake and fire.

For Muir, the plan was the ultimate desecration. With the Sierra Club, which he had co-founded in 1892, he launched a fierce, nationwide campaign to save the valley. He framed the debate as a holy war, writing with apocalyptic fervor against the “temple destroyers” and “devotees of ravaging commercialism” who lifted their eyes not “to the God of the mountains,” but “to the Almighty Dollar”. His most famous cry from the battle became a rallying cry for preservationists everywhere: “Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man”.

Despite a protracted fight, the preservationists lost. The Raker Act, which authorized the dam’s construction, was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson in December 1913. Muir died just one year later, and the loss of Hetch Hetchy is often seen as the great tragedy of his final years. However, the battle itself had a profound and lasting impact. It was the first major national debate over wilderness preservation, raising public consciousness to an unprecedented level and mobilizing a new constituency for the cause. The public outrage over the flooding of a spectacular valley within a national park was a key catalyst for the creation of the National Park Service just three years later in 1916. The new agency was given a clear preservationist mandate, ensuring that such a loss would be far more difficult to justify in the future. In this sense, the defeat at Hetch Hetchy contained the seeds of preservation’s greatest long-term victory.

Part IV: The Enduring and Contested Legacy

A Troubling Silence: Wilderness and the Erasure of Peoples

A critical examination of Muir’s legacy reveals a profound and troubling paradox at the heart of his philosophy. The very concept of “wilderness” that he championed—a pure, pristine, and unpeopled landscape—was predicated on the violent removal and erasure of the Indigenous communities who had inhabited and stewarded those lands for millennia. Yosemite Valley was not an empty wilderness when Muir arrived; it was the homeland of the Ahwahneechee people, who called it Ahwahnee.

Muir’s writings are not merely silent on this history; they are often actively complicit in it. His journals contain derogatory comments about the Native Americans he encountered, describing them as “dirty,” “lazy,” and having “no right place in the landscape”. His vision of a pure wilderness was, in effect, a landscape cleansed of its original human inhabitants, whose presence he saw as a blemish. This romanticized “Muir ideal of the lone white man at one with nature” is an inherently exclusionary and colonialist construct. It created a paradigm in American environmentalism that tragically separated nature from culture and wilderness from humanity. This separation has had long-lasting, damaging consequences for Indigenous peoples and has contributed to making the mainstream environmental movement less welcoming to people of color. The very beauty he celebrated was made possible by a history of violence he largely chose to ignore.

A Reckoning with the Founder

For over a century, these problematic aspects of Muir’s legacy were largely overlooked by the mainstream environmental movement he helped create. That began to change dramatically in July 2020. In the midst of a national reckoning over racial injustice following the murder of George Floyd, the Sierra Club’s then-Executive Director, Michael Brune, issued a public statement acknowledging and apologizing for Muir’s racist statements and the “whiteness and privilege” of the club’s early history.

The statement was a landmark moment. The organization Muir founded was forced to publicly grapple with his full, complicated legacy. Brune wrote that Muir’s words “continue to hurt and alienate Indigenous people and people of color” and committed the organization to investing millions of dollars in racial justice work and diversifying its leadership. The move sparked intense debate. Some members defended Muir as a “man of his time” whose views later evolved, while others argued the reckoning was long overdue and essential for the movement’s future. This ongoing debate illustrates a pivotal shift in 21st-century environmentalism—a move away from a narrow focus on wilderness preservation toward a more integrated, intersectional understanding that sees racial justice, social equity, and Indigenous rights as inseparable from ecological health. Muir’s legacy has become a central battleground in this vital ideological evolution.

Conclusion: Muir in the 21st Century

John Muir remains an indispensable, if complicated, figure in the American story. His core ideas—the profound interconnectedness of all life, the intrinsic value of nature, and the spiritual necessity of wildness—are more urgent and relevant than ever. In an age defined by the existential threats of climate change, mass extinction, and ecological collapse, his passionate call to recognize the sanctity of the natural world provides a powerful philosophical counterpoint to the consumerist and extractivist cultures driving these crises. His famous aphorism, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe,” is a perfect encapsulation of ecological thinking. His writings continue to inspire millions to, as he famously urged, “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings”.

He was a visionary who taught a nation to see its wild landscapes not as commodities to be exploited but as cathedrals to be revered. Yet, he was also a man deeply constrained by the prejudices of his time, and his influential vision of wilderness was tragically incomplete. To read Muir today is to engage with this fundamental tension—to be inspired by his ecstatic love for the wild while simultaneously challenging the exclusionary legacy it helped create. His ultimate relevance lies not in being a flawless saint to be worshipped, but a brilliant, powerful, and deeply flawed prophet whose work we must continue to read, admire, and critically transcend on the path to a more just and sustainable future.

References

- Badè, William Frederic, ed. A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1916.

- Brune, Michael. “Pulling Down Our Monuments.” Sierra Club. July 22, 2020. https://www.sierraclub.org/michael-brune/2020/07/john-muir-early-history-sierra-club.

- Clayton, John. “Frenemies: John Muir and Gifford Pinchot.” National Endowment for the Humanities. Humanities 38, no. 4 (Fall 2017). https://www.neh.gov/article/frenemies-john-muir-and-gifford-pinchot.

- Fears, Darryl, and Steven Mufson. “Sierra Club Grapples With Founder John Muir’s Racism.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 24, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/sierra-club-grapples-founder-john-muirs-racism-180975404/.

- Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. “Sierra Club denounces John Muir’s racist beliefs: The complicated history of Muir Woods.” July 24, 2020. https://www.parksconservancy.org/article/sierra-club-john-muir-racism-history-muir-woods-name.

- Jacobs, Jeremy P. “Sierra Club takes on the racism of founder John Muir.” E&E News by POLITICO, July 22, 2020. https://www.eenews.net/articles/sierra-club-takes-on-the-racism-of-founder-john-muir/.

- Limbaugh, Ronald H. “The Nature of John Muir’s Religions.” The Pacific Historian 29, no. 2/3 (Summer/Fall 1985): 16–29. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=muir-symposium.

- Miller, Char. Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2001.

- Muir, John. My First Summer in the Sierra. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911.

- Muir, John. Our National Parks. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1901.

- Muir, John. The Mountains of California. New York: The Century Co., 1894.

- Muir, John. The Yosemite. New York: The Century Co., 1912.

- National Park Service. “The Fight for Hetch Hetchy.” Environment and Society Portal. Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.environmentandsociety.org/tools/keywords/fight-hetch-hetchy.

- National Park Service. “The Hetch Hetchy Timeline.” John Muir National Historic Site. Last updated July 18, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/jomu/learn/historyculture/the-hetch-hetchy-timeline.htm.

- National Park Service. “Who Was John Muir?” John Muir National Historic Site. Last updated June 12, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/jomu/learn/historyculture/who-was-john-muir.htm.

- Taylor, Stephen J. “Misc. Monday: John Muir’s Vision Lost and Found.” Historic Indianapolis. June 29, 2015. https://historicindianapolis.com/misc-monday-john-muirs-vision-lost-and-found/.

- Tompkins, Lucy. “Sierra Club Says It Must Confront the Racism of John Muir.” The New York Times, July 22, 2020.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Conservation versus Preservation and the U.S. Forest Service.” USDA Blog. August 24, 2016. https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/blog/conservation-versus-preservation.

- Worster, Donald. A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.