The Paradox of Isolation

“We are the ocean, and the ocean is us.” – Epeli Hau’ofa

The Lord Howe Island stick insect, thought extinct for 80 years, clung to existence on Ball’s Pyramid—a volcanic spire rising 562 meters from the Tasman Sea, the world’s tallest sea stack.¹ On this bare rock, 23 kilometers from their ancestral home, fewer than 30 individuals survived beneath a single melaleuca shrub, Earth’s most precarious species redoubt. Their 2001 rediscovery and subsequent captive breeding program—from 2 breeding pairs to over 11,000 individuals—exemplifies Oceania’s central conservation paradox: extreme vulnerability paired with extraordinary resilience.²

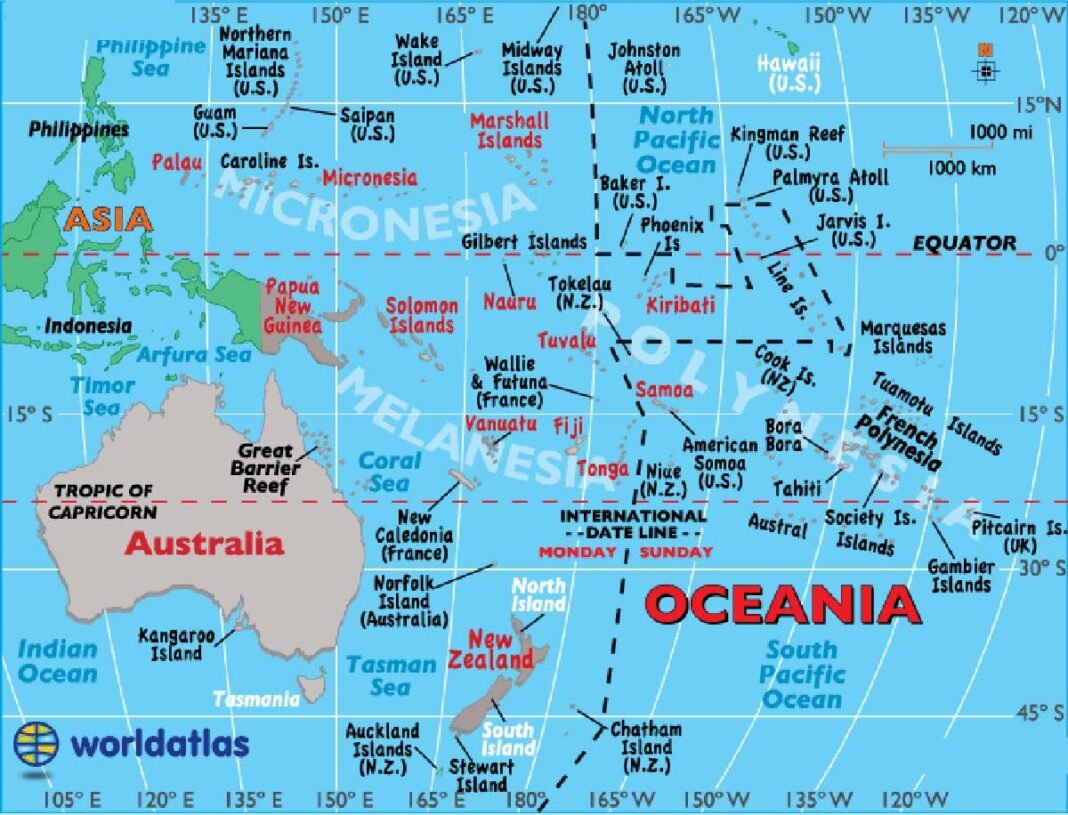

This paradox defines a region spanning 100 million square kilometers of Pacific Ocean, containing 25,000 islands yet comprising only 8.5 million square kilometers of land—smaller than China.³ From Australia’s vast deserts to Kiribati’s atolls barely above sea level, from New Zealand’s temperate rainforests to Papua New Guinea’s glacial peaks, Oceania encompasses Earth’s most extreme environmental gradients and evolutionary experiments. It is simultaneously the planet’s last-colonized region by humans and first to face climate change’s existential threat.⁴

The region presents unique conservation challenges: island species evolved without terrestrial predators, making them fatally naive to introduced mammals; Australia’s ancient soils and erratic climate created ecosystems functioning on minimal nutrients; rising seas threaten to submerge entire nations.⁵ Yet Oceania also offers unparalleled opportunities: islands as restoration laboratories, Indigenous management systems proven over millennia, and some of Earth’s last intact wilderness areas.

Structural Approach: Three Oceanias, Shared Destinies

Given this diversity, we assess Oceania through three distinct yet interconnected lenses:

Section A: Continental Australia—The Dry Frontier

Earth’s driest inhabited continent, where 70% of land receives less than 500mm annual rainfall, yet supporting biodiversity found nowhere else.

Section B: Pacific Island Nations—Arks at Risk

From volcanic high islands to coral atolls, 22 nations and territories facing development pressures and climate catastrophe while maintaining ocean management systems larger than continents.

Section C: New Zealand and Temperate Islands—Evolutionary Laboratories

Isolated landmasses that evolved unique biotas, now leading global restoration innovation through predator eradication and ecosystem reconstruction.

SECTION A: CONTINENTAL AUSTRALIA—THE DRY FRONTIER

1. Historical Baseline

Pre-1750 Wilderness Extent

Before European colonization in 1788, Australia maintained approximately 7.2 million km² of functional wilderness across its 7.69 million km² landmass—over 93% wilderness coverage.⁶ The Great Western Woodlands covered 160,000 km², Earth’s largest intact temperate woodland. The Great Barrier Reef stretched 2,300 kilometers in pristine condition. Tasmania’s wilderness encompassed 2.4 million hectares of Gondwanan rainforest. The Simpson Desert’s 176,500 km² supported stable populations of bilbies, bandicoots, and bettongs now extinct across most ranges.⁷

This apparent wilderness, however, was actively managed landscape. Aboriginal Australians, present for 65,000 years, had fundamentally shaped ecosystems through fire management, selective harvesting, and water manipulation.⁸ Their controlled burning created vegetation mosaics supporting higher biodiversity than “natural” fire regimes. Fire-stick farming maintained open woodlands where closed forest would otherwise dominate. Complex fish trap systems like Brewarrina’s—possibly world’s oldest human construction at 40,000 years—modified river systems while maintaining ecological function.⁹

Megafauna populations tell a story of sustainable coexistence after initial human arrival impacts. Red kangaroo populations numbered 15-20 million, similar to today but distributed more evenly. Koala populations occupied 80% more habitat than currently. Thylacines persisted on mainland until 3,000 years ago, declining after dingo introduction, not human hunting. Marine ecosystems supported dugong populations 10 times current numbers, sea turtle nesting beaches lined the entire eastern coast, and southern right whales calved in every suitable bay.¹⁰

Indigenous Management Systems

Aboriginal Australian land management represented the longest continuous conservation practice on Earth. The Dreaming—a complex spiritual-ecological framework—embedded conservation in culture through sacred sites, seasonal calendars, and totemic responsibilities.¹¹ Each clan maintained detailed ecological knowledge of their Country, understanding plant phenology, animal behavior, water cycles, and fire ecology with scientific precision.

Cool burning in northern savannas reduced greenhouse emissions by 40% compared to wildfires.¹² Desert peoples’ maintenance of water sources through vegetation management supported wildlife populations through droughts. Coastal communities’ selective harvesting of shellfish maintained productive beds for millennia—archaeological middens show consistent species size over 10,000 years, indicating no overexploitation.¹³

The integration of spiritual and practical management created resilient systems. Increase sites—places where ceremonies ensured species abundance—often coincided with breeding grounds requiring protection. Seasonal restrictions on harvesting aligned with reproductive cycles. Traditional ecological calendars recognized 6-8 seasons based on environmental cues rather than arbitrary calendar dates.

2. Current Status Analysis

Quantitative Metrics

Australia retains approximately 3.2 million km² of intact wilderness—44% of historical extent but only 16% meeting strict wilderness quality criteria:¹⁴

• Intact wilderness remaining: 3.2 million km² (44% of historical) • High-quality wilderness (WQI >8): 1.15 million km² (16% of landmass) • Protected areas: 19.6% terrestrial, 36% marine (though only 12% in no-take zones) • Indigenous Protected Areas: 75 million hectares (44% of National Reserve System) • Connectivity index: 3/10 (extreme fragmentation in agricultural zones)

Ecosystem Health Indicators:

- Forest cover: 16% (134 million hectares, 50% of pre-European extent)

- Wetlands: 50% lost, remaining 65% degraded

- Rivers: 23% near pristine, 19% severely modified

- Soil health: 60% of agricultural land degraded

- Great Barrier Reef: 50% coral cover lost since 1995

Species Status:

- Extinctions since 1788: 100+ vertebrates (highest mammal extinction rate globally)

- Threatened species: 1,900+ listed, likely 3,000+ in reality

- Range contractions: Average 40% for native mammals

- Population declines: 70% average for threatened birds

Qualitative Assessment

Australia faces an extinction crisis unparalleled in the developed world. The 2019-2020 Black Summer bushfires burned 18.6 million hectares, killed 3 billion vertebrates, and pushed 113 species toward extinction.¹⁵ These fires, following unprecedented drought, demonstrated ecosystem vulnerability to climate extremes.

Yet remote Australia maintains vast intact ecosystems. The Great Western Desert’s 450,000 km² remains largely unmodified. Cape York Peninsula supports wilderness from mountains to reef. The Kimberley’s 423,000 km² maintains functional ecosystems despite increasing pressure. These areas, often on Indigenous lands, represent global conservation priorities.

Agricultural zones tell a different story. The Murray-Darling Basin, producing 40% of Australia’s agricultural output, faces ecological collapse from over-extraction, salinization, and climate change.¹⁶ The Western Australian wheatbelt cleared 18 million hectares in 50 years, creating one of world’s most fragmented landscapes. Tasmania’s old-growth forests continue falling despite decades of protests.

3. Conservation Successes

Protected Area Achievements

Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) revolutionized Australian conservation, combining traditional management with modern science across 75 million hectares.¹⁷ These areas, managed by Traditional Owners, achieve better conservation outcomes than government parks while supporting Indigenous livelihoods and cultural transmission.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, despite reef decline, demonstrates large-scale marine protection possibilities. Its 344,400 km² zoning system balances conservation with sustainable use, generating AU$6.4 billion annually while protecting 3,000 coral reefs.¹⁸

Private conservation contributes significantly through organizations like Bush Heritage Australia (11.3 million hectares) and Australian Wildlife Conservancy (7.8 million hectares).¹⁹ These groups achieve measurable conservation outcomes through scientific management, controlling 30% of Australia’s conservation estate outside government parks.

Species Recovery Programs

Eastern barred bandicoot recovery from 150 individuals to 1,500 through captive breeding and predator-proof reserves demonstrates possibilities when resources align.²⁰ Malleefowl conservation through community monitoring and habitat protection stabilized populations across 500,000 km².

Tasmanian devil facial tumor disease response—establishing insurance populations, developing vaccines, and maintaining genetic diversity—provides a model for disease management in wildlife.²¹ The program maintains hope for devil survival despite 80% population decline.

Marine success stories include humpback whale recovery from 500 to 40,000 individuals through protection, and southern right whale population growth at 7% annually.²² Grey nurse shark protection through critical habitat designation reversed population decline.

SECTION B: PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS—ARKS AT RISK

1. Historical Baseline

Pre-Contact Wilderness

Pacific islands before human arrival represented Earth’s most isolated evolutionary experiments. Each archipelago evolved unique biotas from limited colonizers—Hawaii from 300 original species developed 10,000 endemic species over 5 million years.²³ New Caledonia, isolated for 80 million years, evolved flora 83% endemic. Fiji’s isolation produced the world’s most primitive flowering plants.

These pristine ecosystems supported extraordinary species radiations. Hawaii’s honeycreepers diversified into 50+ species from a single finch ancestor. New Zealand’s 245 bird species included giants—moa reaching 3.6 meters tall, Haast’s eagle with 3-meter wingspan.²⁴ Pacific islands hosted 1,000+ endemic land snail species, many single-valley endemics. Coral atolls, though species-poor terrestrially, supported rich marine ecosystems—single atolls containing 500+ fish species.

Human arrival triggered extinction waves. Polynesian colonization (3,500-700 years ago) eliminated 1,000+ bird species—10% of global avifauna.²⁵ Megafauna disappeared rapidly: moa within 200 years of Maori arrival, giant tortoises from Vanuatu, crocodiles from New Caledonia. Yet Polynesian societies developed sustainable systems after initial impacts, maintaining stable populations and ecosystems for centuries before European contact.

Traditional Management Systems

Pacific islanders developed sophisticated resource management from necessity—island resources were finite and visible. The ahupua’a system in Hawaii managed watersheds from mountain to reef as integrated units.²⁶ Tabu (sacred restrictions) protected spawning grounds and nursery areas. Rahui in Polynesia closed areas for regeneration. These systems, embedding conservation in spiritual practice, maintained resources for generations.

Traditional ecological knowledge encoded in oral traditions preserved detailed environmental information. Marshallese stick charts mapped ocean swells and currents with stunning accuracy. Polynesian navigators recognized 200+ stars, understanding their movements and associated weather patterns. Knowledge of species behavior, seasonal cycles, and ecological relationships matched or exceeded modern science.

2. Current Status Analysis

Quantitative Metrics

Pacific islands face unprecedented pressures from development, invasive species, and climate change:

• Remaining native forest: 23% of historical extent • Intact coral reefs: 30% in good condition, 40% severely degraded • Protected areas: 5.4% terrestrial, 1.9% marine (far below targets) • Endemic species threatened: 45% of birds, 60% of land snails • Invasive species established: 2,000+ across region

Climate Change Impacts:

- Sea level rise: 3.4mm/year (double global average in some areas)

- Ocean temperature: +0.8°C since 1950, accelerating

- Ocean acidification: pH decreased 0.1 units (30% increase in acidity)

- Extreme events: Category 5 cyclones increased 15% per decade

- Coral bleaching: Major events 1998, 2002, 2016, 2020, 2024

Qualitative Assessment

Pacific islands epitomize the climate crisis frontline. Tuvalu and Kiribati face complete submersion within decades. Marshall Islands’ freshwater lenses shrink from saltwater intrusion. Coastal communities relocate inland as king tides flood villages. These impacts occur despite Pacific islands contributing <0.03% of global emissions.²⁷

Yet Pacific leadership in ocean conservation inspires globally. The Pacific Oceanscape covers 40 million km²—10% of Earth’s surface—in coordinated marine management.²⁸ Palau’s National Marine Sanctuary protects 500,000 km² (80% of its EEZ) from commercial fishing. The Cook Islands’ Marae Moana encompasses 1.9 million km² in multiple-use marine park.

Invasive species remain the primary terrestrial threat. Rats occur on 80% of Pacific islands, devastating seabirds and native plants. Little fire ant spreads across archipelagos, transforming ecosystems. Strawberry guava forms impenetrable thickets eliminating native forest. Without biosecurity improvement, remaining native ecosystems face certain degradation.

3. Innovative Solutions

Large-Scale Marine Protection

Pacific nations lead global marine conservation through unprecedented protection scales. Kiribati’s Phoenix Islands Protected Area (408,250 km²) demonstrates small nations can protect vast areas.²⁹ French Polynesia’s 5 million km² EEZ includes 1 million km² of protection. These areas, managed through traditional and modern approaches, maintain ocean health while supporting livelihoods.

Regional cooperation through the Nauru Agreement controls 25% of global tuna supply through coordinated management.³⁰ Vessel Day Scheme licensing increased revenue 500% while maintaining stocks. This demonstrates small nations collectively wielding significant conservation influence.

Island Restoration Innovation

Invasive species eradication transforms island conservation. New Zealand eliminated rats from 200+ islands, with Campbell Island (11,300 hectares) the largest successful rodent eradication.³¹ France eradicated rabbits, rats, and mice from Kerguelen (7,215 km²). These successes enable ecosystem recovery—seabird populations increasing 200-300% post-eradication.

Genetic rescue saves species from extinction. Norfolk Island green parrot recovery from 32 to 300 birds through genetic management maintains viability.³² Black robin recovery from single breeding pair (Old Blue) to 250 individuals demonstrates extreme intervention success. These programs provide templates for saving critically endangered species globally.

SECTION C: NEW ZEALAND AND TEMPERATE ISLANDS—EVOLUTIONARY LABORATORIES

1. Historical Baseline

Pre-Human Paradise

New Zealand before human arrival 750 years ago supported ecosystems unlike anywhere on Earth. Without terrestrial mammals except three bat species, birds filled all ecological niches—moa as browsers, kakapo as seed dispersers, kiwi as soil engineers.³³ Forests covered 85% of land area (23 million hectares), from subtropical kauri forests to temperate Nothofagus rainforests. Wetlands covered 10% of land area. Rivers ran clear from mountains to sea through unbroken forest.

This isolation produced extraordinary endemism—80% of vascular plants, 100% of reptiles and amphibians, 90% of insects found nowhere else.³⁴ Tuatara, unchanged for 200 million years, represented an entire reptilian order. Giant weta filled rodent niches. Carnivorous snails hunted earthworms. This evolutionary laboratory demonstrated alternative paths life might take without mammalian dominance.

Subantarctic islands maintained similar isolation. Macquarie Island’s 34 km² supported millions of seabirds without terrestrial predators. Auckland Islands hosted flightless ducks, rails, and the world’s rarest penguin. These islands, scattered across the Southern Ocean, served as stepping stones for marine life between continents.

Maori Environmental Relations

Maori arrival initiated New Zealand’s first extinction wave but also established sustainable management systems. After eliminating moa and other megafauna within 200 years, Maori society developed conservation practices maintaining stable ecosystems for 500 years before European arrival.³⁵

Kaitiakitanga—guardianship rather than ownership—embedded conservation in cultural practice.³⁶ Rahui (temporary restrictions) allowed resource recovery. Whakapapa (genealogical connections) linked human and natural worlds. Traditional ecological knowledge preserved in oral traditions guided sustainable harvesting. These practices maintained forest cover at 50% despite supporting 100,000-200,000 people.

2. Current Status Analysis

Quantitative Metrics

New Zealand’s conservation estate covers unprecedented proportions yet faces ongoing degradation:

• Protected areas: 32% terrestrial (8.6 million hectares) • Native forest remaining: 6.5 million hectares (28% of historical) • Wetlands: 10% of historical extent remain • Threatened species: 4,000+ (74% of vertebrates) • Predator-free islands: 100+ (from zero in 1960)

Invasive Species Impacts:

- Mammalian predators: 30 million possums, 2.5 million rats

- Browsing mammals: 1 million deer, 150,000 goats

- Plant invaders: 2,500+ naturalized species

- Economic cost: NZ$3.3 billion annually

- Conservation cost: NZ$70 million annual predator control

Qualitative Assessment

New Zealand demonstrates both conservation innovation and ongoing crisis. Despite extensive protection, ecosystems continue degrading from invasive species. Forests appear intact but lack understory regeneration from browsing. Bird populations decline despite predator control. Freshwater quality deteriorates from agricultural intensification—cattle increasing from 3 million to 10 million in 30 years.³⁷

Yet New Zealand leads global restoration innovation. Zealandia sanctuary’s 225 hectares in Wellington demonstrates urban rewilding possibilities.³⁸ Predator-proof fencing technology enables mainland islands—areas functioning as if predator-free. Community conservation groups manage 5,000+ projects. School programs connect children with native species many had never encountered.

3. Predator Free 2050 Vision

The Audacious Goal

Predator Free 2050—eliminating rats, possums, and stoats from New Zealand’s 268,000 km²—represents history’s most ambitious conservation project.³⁹ This goal, deemed impossible by many, would restore ecosystems to pre-human function while maintaining modern society.

Early successes demonstrate feasibility. Miramar Peninsula (Wellington) achieved rat eradication across 800 hectares of urban area.⁴⁰ Great Barrier Island’s 28,500 hectares undergoes staged eradication. Genetic technologies like gene drives offer potential breakthrough solutions, though requiring careful ethical consideration.

Innovation Cascade

The program catalyzes conservation innovation globally applicable. Self-resetting traps reduce labor 90%. Thermal imaging drones locate surviving individuals. Environmental DNA detects presence below visual detection. Behavioral lures exploit predator psychology. These technologies, developed for New Zealand, enable conservation globally.

Social innovation matches technological advancement. Community groups adopt 40,000 hectares annually for predator control. Backyard trapping engages urban populations. Schools run breeding programs for native species. This social movement transforms conservation from government responsibility to societal mission.

Integration: Ocean Bridges and Shared Futures

Climate Change: The Existential Threat

Climate change threatens Oceania’s wilderness disproportionately. Australia’s temperatures increased 1.44°C since 1910, with extremes intensifying.⁴¹ Pacific islands face submersion, with Tuvalu potentially uninhabitable by 2050. New Zealand’s glaciers lost 30% of volume in 40 years. These changes cascade through ecosystems evolved in stable climates.

Ocean changes compound terrestrial impacts. Marine heatwaves devastate coral reefs—back-to-back bleaching events allowing no recovery. Ocean acidification threatens shell-forming organisms fundamental to marine food webs. Shifting currents alter nutrient distribution, affecting entire ocean basins. These changes occur faster than species can adapt, ensuring ecosystem transformation regardless of conservation efforts.

Yet Oceania demonstrates resilience. Traditional knowledge guides adaptation—Kiribati’s president advocates “migration with dignity” while maintaining culture.⁴² Australia’s Indigenous rangers combine traditional burning with satellite monitoring for fire management. New Zealand integrates mātauranga Māori (Maori knowledge) with Western science for ecosystem restoration.

Regional Cooperation Imperatives

Oceania’s shared challenges demand unprecedented cooperation. Migratory species connect all nations—whales, seabirds, sea turtles crossing boundaries. Ocean currents distribute impacts regionally—plastic from one nation affecting all. Climate change respects no borders.

Existing frameworks provide foundation: Pacific Regional Environment Programme coordinates 26 nations; Coral Triangle Initiative links six nations protecting 75% of coral diversity; Trans-Tasman agreements enable biosecurity cooperation.⁴³ These must expand rapidly to match threat scales.

Financial innovation could transform conservation. Blue bonds fund marine protection while providing returns. Carbon credits from intact forests generate revenue exceeding logging. Nature-based tourism, generating US$42 billion annually pre-pandemic, demonstrates economic value of intact ecosystems.⁴⁴

The 2050 Vision: Archipelagic Hope

By 2050, Oceania could model wilderness recovery for the world. Australia’s rewilding programs could restore ecosystems across millions of hectares, with species returning from extinction’s brink. Pacific islands could maintain ocean health through Indigenous management systems scaled with modern technology. New Zealand could achieve predator-free status, restoring birdsong silent for centuries.

This vision requires transformation beyond conservation. Economic systems must value ecosystem services above extraction. Governance must empower Indigenous peoples as primary land managers. Technology must serve ecological recovery rather than exploitation. Most fundamentally, the relationship between humans and nature must shift from domination to partnership.

The Lord Howe Island stick insect’s recovery from 2 individuals to thousands demonstrates that no situation is hopeless with sufficient commitment. Oceania’s wilderness, evolved in isolation, adapted to extremes, managed by the world’s oldest cultures, offers not just regional but global hope. In protecting these island arks and continental extremes, humanity protects possibilities for Earth’s future.

References

¹ Priddel, David, et al. “Rediscovery of the ‘Extinct’ Lord Howe Island Stick Insect.” Nature Australia 27, no. 1 (2002): 30-37.

² Honan, Patrick. “The Lord Howe Island Stick Insect: An Extraordinary Conservation Success Story.” Austral Entomology 47, no. 1 (2008): 1-11.

³ Neall, Vincent E., and Steven A. Trewick. “The Age and Origin of the Pacific Islands: A Geological Overview.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 363, no. 1508 (2008): 3293-3308.

⁴ Nunn, Patrick D. “The End of the Pacific? Effects of Sea Level Rise on Pacific Island Livelihoods.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 34, no. 2 (2013): 143-171.

⁵ Kingsford, Michael J., et al. “Major Conservation Policy Issues for Biodiversity in Oceania.” Conservation Biology 23, no. 4 (2009): 834-840.

⁶ Bradshaw, Corey J. A. “Little Left to Lose: Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Australia since European Colonization.” Journal of Plant Ecology 5, no. 1 (2012): 109-120.

⁷ Johnson, Chris. Australia’s Mammal Extinctions: A 50,000 Year History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

⁸ Gammage, Bill. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2011.

⁹ Builth, Heather, et al. “Environmental and Cultural Change on the Mt Eccles Lava-Flow Landscapes of Southwest Victoria, Australia.” The Holocene 18, no. 3 (2008): 413-424.

¹⁰ Flannery, Tim. The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People. Port Melbourne: Reed Books, 1994.

¹¹ Rose, Deborah Bird. Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness. Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission, 1996.

¹² Russell-Smith, Jeremy, et al. “Managing Fire Regimes in North Australian Savannas: Applying Aboriginal Approaches to Contemporary Global Problems.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11, no. 1 (2013): e55-e63.

¹³ Ulm, Sean. “Australian Marine Reservoir Effects: A Guide to ΔR Values.” Australian Archaeology 63, no. 1 (2006): 57-60.

¹⁴ Watson, James E. M., et al. “Wilderness and Future Conservation Priorities in Australia.” Diversity and Distributions 15, no. 6 (2009): 1028-1036.

¹⁵ Wintle, Brendan A., et al. “After the Megafires: What Next for Australian Wildlife?” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 35, no. 9 (2020): 753-757.

¹⁶ Grafton, R. Quentin. “Water Reform in the Murray-Darling Basin.” Water Resources Research 55, no. 1 (2019): 1-12.

¹⁷ Gorenflo, L. J., et al. “Co-occurrence of Linguistic and Biological Diversity in Biodiversity Hotspots and High Biodiversity Wilderness Areas.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, no. 21 (2012): 8032-8037.

¹⁸ Deloitte Access Economics. “At What Price? The Economic, Social and Icon Value of the Great Barrier Reef.” Brisbane: Deloitte, 2017.

¹⁹ Fitzsimons, James A. “Private Protected Areas in Australia: Current Status and Future Directions.” Nature Conservation 10 (2015): 1-23.

²⁰ Hill, Richard, et al. “Recovery of the Eastern Barred Bandicoot in Victoria.” In Recovering Australian Threatened Species, edited by Stephen Garnett et al., 259-268. Clayton: CSIRO Publishing, 2018.

²¹ McCallum, Hamish, et al. “Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumour Disease: Lessons for Conservation Biology.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 23, no. 11 (2008): 631-637.

²² Noad, Michael J., et al. “Absolute and Relative Abundance Estimates of Australian East Coast Humpback Whales.” Journal of Cetacean Research and Management Special Issue 3 (2011): 243-252.

²³ Ziegler, Alan C. Hawaiian Natural History, Ecology, and Evolution. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002.

²⁴ Worthy, Trevor H., and Richard N. Holdaway. The Lost World of the Moa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

²⁵ Steadman, David W. Extinction and Biogeography of Tropical Pacific Birds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

²⁶ Kirch, Patrick V. “Hawaii as a Model System for Human Ecodynamics.” American Anthropologist 109, no. 1 (2007): 8-26.

²⁷ IPCC. “Small Islands.” In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, 2043-2121. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

²⁸ Pratt, Christina, et al. “The Pacific Oceanscape: A Framework for Conservation and Management.” Ocean & Coastal Management 168 (2019): 238-248.

²⁹ Rotjan, Randi D., et al. “Establishment, Management, and Maintenance of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area.” Advances in Marine Biology 69 (2014): 289-324.

³⁰ Yeeting, Agnes D., et al. “Implications of New Economic Policy Instruments for Tuna Management in the Western and Central Pacific.” Marine Policy 63 (2016): 45-52.

³¹ Towns, David R., et al. “From Small Maria to Massive Campbell: Forty Years of Rat Eradications from New Zealand Islands.” New Zealand Journal of Zoology 40, no. 4 (2013): 377-399.

³² Ortiz-Catedral, Luis, et al. “Conservation Status and Ecology of the Norfolk Island Green Parrot.” Emu 118, no. 3 (2018): 264-274.

³³ Gibbs, George. Ghosts of Gondwana: The History of Life in New Zealand. Nelson: Craig Potton Publishing, 2016.

³⁴ McGlone, Matt S., et al. “The Vegetation Cover of New Zealand during the Last Glacial Maximum.” Quaternary Science Reviews 74 (2013): 202-214.

³⁵ Anderson, Atholl. “The Making of the Maori Middle Ages.” Journal of New Zealand Studies 23 (2016): 2-18.

³⁶ Roberts, Mere, et al. “Kaitiakitanga: Maori Perspectives on Conservation.” Pacific Conservation Biology 2, no. 1 (1995): 7-20.

³⁷ Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. “Water Quality in New Zealand: Land Use and Nutrient Pollution.” Wellington: PCE, 2015.

³⁸ Campbell-Hunt, Diane. “Developing a Sanctuary: The Karori Experience.” Victoria University of Wellington Law Review 33 (2002): 255-276.

³⁹ Russell, James C., et al. “Predator-Free New Zealand: Conservation Country.” BioScience 65, no. 5 (2015): 520-525.

⁴⁰ Peters, Mark A., et al. “Rat Eradication on Miramar Peninsula, Wellington, New Zealand.” Conservation Evidence 18 (2021): 20-27.

⁴¹ CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology. “State of the Climate 2022.” Canberra: Australian Government, 2022.

⁴² Farbotko, Carol, and Heather Lazrus. “The First Climate Refugees? Contesting Global Narratives of Climate Change in Tuvalu.” Global Environmental Change 22, no. 2 (2012): 382-390.

⁴³ SPREP. “State of Conservation in Pacific Islands: 2020 Regional Report.” Apia: Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme, 2021.

⁴⁴ UNWTO. “Tourism in Small Island Developing States: Building a More Sustainable Future.” Madrid: World Tourism Organization, 2020.